The Cottage Industry. The Indian Corps Bomb Factory. (Chap.1 Pt.2)

“All things bright and beautiful. Gadgets great and small. Bombs, grenades, and trench boards, the sappers make them all. ”

The Cottage Industry.

Sir John French first wrote to the War Office in November 1914 requesting the provision of trench mortars to deal with enemy trenches such as those encountered during the Battle of the Aisne, but the War Office and the Royal Ordnance Factories at Woolwich were reluctant to commit resources to supply of a new weapon system to the army. There were concerns about the time required to equip and train the army in a new weapon while it was already engaged in active operations, the diversion of scarce resources from the production of field artillery to the manufacture of trench mortars and last, but not least, concerns about how long the period of trench warfare would last for General Joffre had declared that he would renew the offensives when the weather improved in the spring. With the supply of any new weapons receding into the future the troops in the trenches resorted to manufacturing their own trench warfare munitions, first grenades, then trench mortars. This activity I refer to as the Cottage Industry.

The Tactical Imperative.

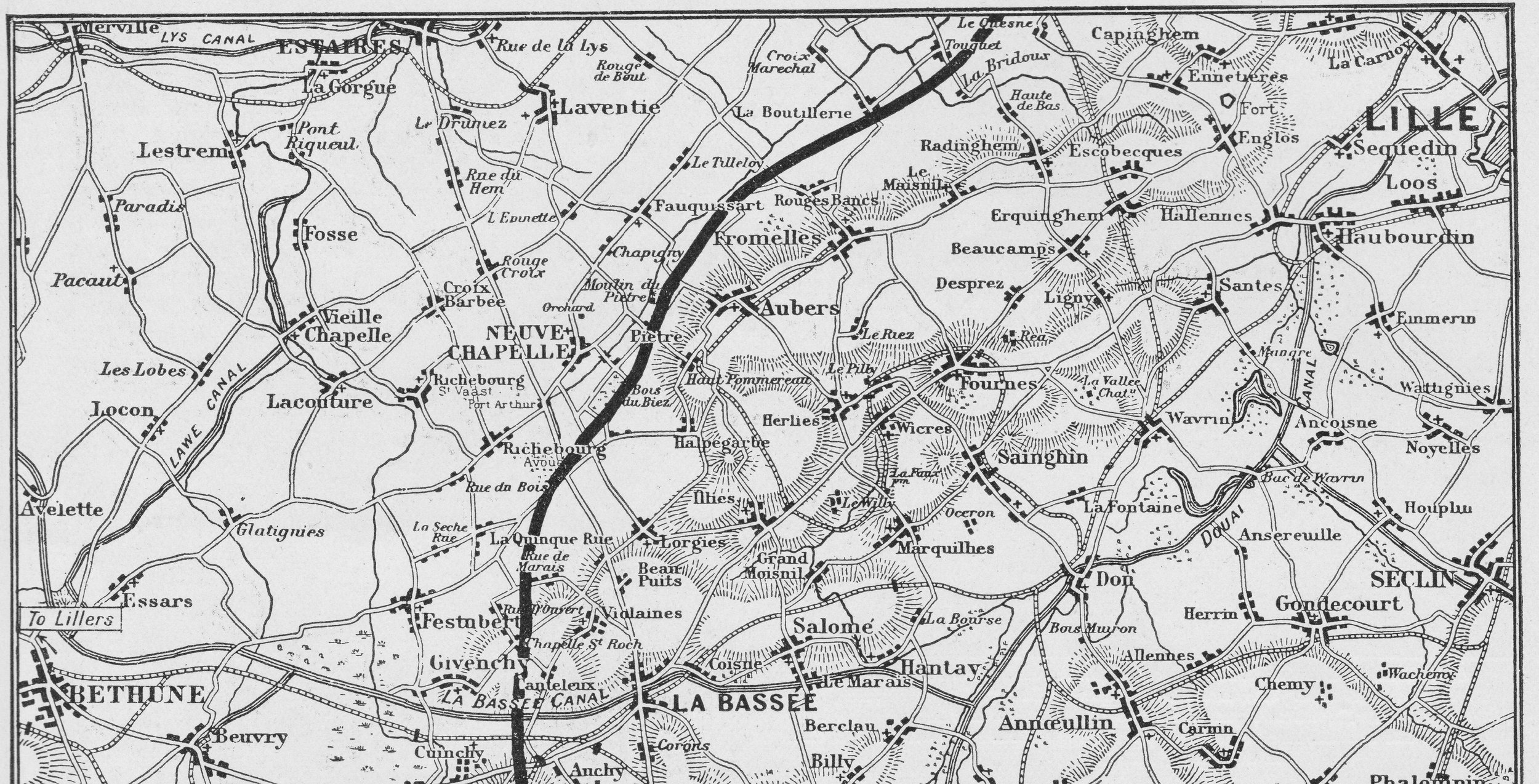

During the First Battle of Ypres (19 October-22 of November 1914), the BEF’s experience of trench fighting was limited to firing from rifle pits and ditches in what was essentially a battle of manoeuvre. At the end of the battle, the exhausted and depleted BEF went into reserve to be reinforced and re-equipped, while the front line in Flanders was held by the French, except for that portion north of La Bassée, which the Indian Corps occupied. It was to be the fate of these troops to be the first in the BEF to experience static trench warfare, and it is from this experience that they identified the tactical imperatives that gave rise to the demand for grenades and trench mortars. This early battle zone was not the devastated landscape of later years, but still identifiable as farmland with hedges, woods, and many cottages and farm buildings still standing. Although damaged, these provided ample cover for German snipers, machine guns, and concealed entrances to the numerous saps that snaked out towards the Indian firing line.[1]

Field defences on both sides of No Mans Land were practically non-existent, consisting of a few strands of barbed wire strung on wooden frames, termed chevaux de frise, which, as they were not securely fixed to the ground, could be easily pulled aside to create a passage. In many places the trenches were close, no more than 50 to 100 yards apart, which provided a rich environment of potential targets, such as working parties, saps, machine gun positions, snipers and the general infrastructure behind the firing trench such as dugouts and store dumps all within range of trench mortars with a maximum range of about 400 yards emphasising that with the early trench mortars range was less of an issue than the ability to deliver accurately a payload heavy enough to do some damage. In early 1915 one particular length of front occupied by the Indian Corps, around the village of Festubert, was a section where trench-to-trench fighting was particularly personal and aggressive, probably resulting from the closeness of the trenches and a belief among German infantry that they were engaging savage native troops with a reputation for ferocity and bravery, with a less reputable, and erroneous, one for mutilating the wounded and prisoners that fell into their hands.

One of the greatest dangers was the German saps used as bombing stations to shower the Indian trenches with grenades, or to serve as drilling platforms for hand-driven earth augers that drove small tunnels under the Indian parapets which were converted into mines by pushing explosives up to the end blowing in a section of the trench, killing or injuring the garrison. With the trenches so close together, it was rarely possible to use artillery to destroy such saps. In the absence of effective trench mortars and hand grenades, the only alternative was to mount costly, overground raids to fill the saps in. Although few German sapheads were occupied during the night, they were all sited so that the sapheads were protected by crossfire from two or more machine guns, which would immediately open fire if the listeners, usually positioned where the sap crossed the German wire, detected any suspicious noise or movement.

The Indian Corps.

When we come to consider the development of extemporised weapons in the BEF, pride of place goes to the Indian Corps. Although not the first to make jam tin grenades on the Western Front, that accolade goes to I Corps on the Aisne, the Indian Corps were the first to organise their manufacture as a significant activity in dedicated “bomb factories” and developed the tactics from which all subsequent use of hand grenades and trench mortars would derive.

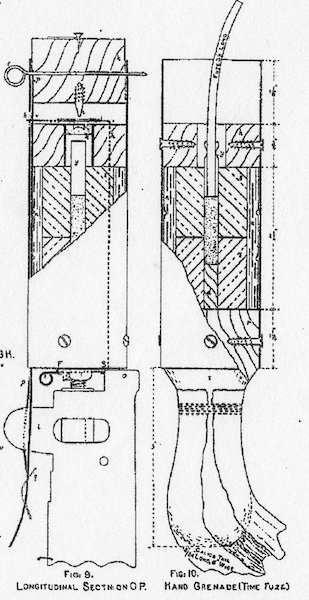

The Royal Engineers of the Indian Corps retained the archaic title of Sappers and Miners, tracing their ancestry back several hundred years to the original creation of armies by the British East India Company. From 1740 onwards, they were organised into three Corps of Sappers and Miners, one each for the Bengal, Madras, and Bombay East Indian Company’s Presidencies. Each Corps consisted of several companies of native craftsmen, commanded by British-trained Royal Engineers who had applied to serve in these highly desirable posts, which promised excitement through action and riches through plunder. From their earliest days, they were renowned for their skills and bravery while on campaign. Before the war the Sappers and Miners, like other troops in India, were trained to fight a European style war against the current bogeyman of the British Imperial Administration, Russia. Unlike the home-based training the Indian army appears to have received some rudimentary training in trench warfare as demonstrated by the activities of the 1st King George’s Own while at Karachi waiting to board ship for Europe. Here, they took the opportunity to train their recruits and reservists in the art of trench construction. When that exercise was complete, they used the trenches to initiate their infantry into the intricacies of trench warfare.[2] They were also familiar with the practice of producing extemporised grenades while on campaign for bone of their day jobs was carrying out punitive expeditions against the Afridis, or one of the other great clans, who frequently demonstrated their resistance to the Government of India’s attempts to exercise control over their traditional tribal areas along the North West Frontier with Afghanistan, basically a form of warfare of skirmishing at close quarters with an enemy skilled in taking cover behind natural defences such as boulders. For the Sappers and Miners details of the construction and performance of hand and rifle grenades, fitted with either a percussion or time fuse, and simple enough to be extemporised during a campaign from materials normally carried by the Field Companies were standard practice. An example was published by Major R. L. McClintock of the Madras Sappers and Miners, the inventor of the Bangalore torpedo just as war broke out in Europe.[3]

[1] TNA: WO95/3936: 7th (Meerut) Division. War Diary Commander Royal Engineers, November 1914.

[2] TNA: WO95/3938: No 3 Field Coy, 1st King George’s Own Sappers and Miners, War Diary, entries for August 13-16, 1914

[3] R.L.McClintock, An Extemporised Hand Grenade, The Royal Engineers’ Journal, April 1913, pp. 193-200 and ‘An Extemporised Rifle Grenade. The Bangalore “Universal” Grenade’, The Royal Engineers’ Journal November 1914, pp. 281-294

Improvised rifle grenade (Fig 8) and hand grenade (Fig 10) developed by Major R.L. McClintock. Note the safety pin and cartridge case primer on the rifle grenade. For the percussion fuse he used a cut-down base of a .303 cartridge its fuze and primer attached to a length of safety fuse. A similar method was employed by Captain Newton in his ‘Pippin’ grenade.

The Indian Expeditionary Force A that came to fight on the Western Front in 1914 was composed of the Lahore Division, supported by the 20th and 21st Companies Bombay Sappers and Miners, and the Meerut Division, supported by No 3 and 4 Companies 1st King George’s Own Sappers and Miners, while the Indian cavalry units were supported by their own Field Companies which were often diverted to support the infantry, both British and Indian.

The Indian Corps disembarked at Marseilles on 26 September 1914 and, with little acclimatisation, and still lacking some essential equipment for operating on the Western Front, were rushed northwards to ‘putty-up’ the crumbling British line during the First Battle of Ypres. For almost a month the Indian Corps remained scattered, attached to British units in urgent need of support but, towards the end of October, reassembled to relieve the exhausted and depleted battalions of the British II and III Corps holding the line between the town of Éstaires and the village of Festubert close to the La Bassée canal and adjoining the trenches of the French 10th Army. With this move the Indian Corps became the first formation in the BEF to experience the full impact of trench warfare. Consequently, they became major innovators in developing equipment and infantry tactics suited to this new form of warfare. The Sappers and Miners (Royal Engineers) of the Meerut Division were the first troops in the BEF to develop a bomb factory for the manufacture of jam pot and hairbrush hand grenades and developed the first trench mortars to be fired in anger at the enemy, and were responsible for the introduction and training of the other Divisions in the BEF in this new technology.

The Battlefield of the Indian Corps. The Great War. Part 68. 4 December 1915. (London: Amalgamated Press Ltd) p.104. NOTE: For illustration only. In 1914 the front line was more to the left of Neuve Chapeele with the Germans in possession of the village.

The Bomb Factories.

King George’s Own Sappers and Miners of the Meerut Division completed the move to their billeting area at Le Touret on the evening of October 31st and, three days later, the War Diary of No 4 Field Company records the manufacture and use of hand grenades complete with a small sketch of their pattern of jam-tin grenade which, with little alteration, was adopted throughout the BEF.[1] From that date onwards, at least one section of the Company was allocated to grenade production.

McClintock’s design was not adopted, probably because he stated that it took about four hours to produce one grenade and, with such a time commitment, they could not have met the divisional demand for 4,000 grenades a week. A simpler design was required one assembled by parties of unskilled infantry under conditions that resembled a production line from materials such as wire, nails, wood for the hairbrush pattern and tin sheeting for the bomb casings, that could be sourced from local French suppliers, supplemented by salvage arrangements for the collection of tin cans for the grenade and bomb casings. While it is difficult to estimate the volume of munitions produced, some idea may be obtained from Colonel Twinning’s weekly shopping list,

Gun Cotton, 2,100 lbs; 3,500 1 oz primers; 1,500 detonators Mk VII; 420 feet safety fuse; 28 dozen boxes of fuses; Three and a half miles of 14 swg wire for binding the hairbrush grenades.[2]

Three patterns of grenades were produced that underwent continuous experimentation to improve functionality. There was the standard jam-tin grenade, which has entered the mythology of the war as one of its archetypal artefacts. Some of these were converted into rifle grenades by screwing a metal rod onto the base similar to the Hales rifle grenade. Also popular was the hairbrush pattern. A short piece of wooden plank shaped at one end into a short throwing handle like a table tennis bat. To this, wrapped around with wire, was a tobacco tin surrounded by large nails to act as shrapnel, filled with high explosive and fitted with detonator and fuse. This popular grenade, although heavier, could be thrown further than the jam tin and easier to throw from a trench. Finally, there was the fragmentation or pipe bomb, a short length of cast iron pipe deeply scored up and down and round to increase fragmentation and strapped to a throwing handle like the hairbrush. All patterns used a time fuse but, in their search for improvements, the Sappers and Miners successfully completed trials with a percussion fuse on December 2nd, although this was not adopted, probably because it was too difficult and slow to manufacture under field conditions.

[1] TNA: WO95/3938: No 3 Field Coy 1st King George’s Own Sappers and Miners. War Diary, Entry for 3-5 November 1914

[2] TNA: WO95/3935: Commander Divisional Engineers HQ, 7th (Meerut) Division. War Diary, December 1914

(A) Indian Corps Jam Tin Hand Grenade. (B) Indian Corps Hairbrush Hand Grenade. Produced by the Sappers and Miners, Lahore Division. TNA: WO95/3919 War Diary 20th Coy. 3rd Sappers and Miners, Jan.1915.

The resources to create a dedicated bomb factory, the first in the BEF, became available following the arrival of the British Eighth Division in November 1914. They took over the line from Éstaires to Neuve Chappelle, the two divisions of the Indian Corps concentrating on the line Neuve Chappelle to Festubert. Following this shortening of their line, the Indian Corps underwent a reorganisation. Each division would hold the front line in rotation; the division not in the line would rest or train. The Sappers and Miners required a more drastic reorganisation as they were approaching a manpower crisis. Ever since their arrival in the battle zone, they had lost skilled men to illness and casualties, and replacements by trained reinforcements from India were problematic; worse still was the condition of the 20th and 21st Companies of the Bombay Sappers and Miners, attached to the Lahore Division. They had lost more than half their strength and almost all their offices, British and Indian, when deployed as assault troops in the abortive attempt to recapture Neuve Chappelle on October 28th.

The solution was to treat the four companies as one organisation with a rota set up to support the division in the trenches. The Sappers and Miners, not on trench duty, introduced two innovations into the BEF. During this early part of the war many frontline activities, such as digging and repairing trenches and saps, making shelters, putting out wire, repairing roads, etc, that would become the responsibility of the infantry or specialised pioneer battalions, were carried out by the Sappers of the Royal Engineer Field Companies, but by late October many were seriously understrength, having lost officers and key personnel through sickness and casualties, Throughout November, the demand for field engineering increased as the nature of trench warfare became better understood and, the frontline trench system became more complex, the Sappers Miners struggled to find the resources to meet the increased commitments. It dawned on them that, as much of the work was unskilled, it could be carried out by the infantry and a training program was instituted for the battalions out of the line, making them responsible for routine trench digging, carrying out minor repairs to damage inflicted by enemy action and laying out and repairing the wire in front of their trenches.

The second innovation was more revolutionary. In 1914, army doctrine held that grenades were weapons employed by trained combat engineers, not infantry. While this may have been a sensible precaution when throwing the complex No.1 percussion grenade, this practice continued following the introduction of the first extemporised time-fused hand grenades. It was the practice to store such grenades close to the front line, and when the infantry identified a suitable target, they would send for a Sapper, who would take a grenade from the store, light it, and throw it toward the target. Such a procedure had several drawbacks. If the proposed target was transient, such as an enemy working party, it may have moved out of range before the bomb-throwing Sapper appeared. It also increased the danger to the highly trained Sappers, as anyone seen attempting to throw a bomb would immediately become a target for every enemy sniper within range, and calling on a Sapper to come and throw a grenade would take him away from other important work, usually in the bomb factory. The officers of the Indian Corps, appreciating that their extemporised jam tin and hairbrush grenades were simple to use, took a pragmatic approach to their use. Discarding the rulebook, the Sappers and Miners were ordered to start training selected infantrymen to form battalion bombing squads, the first training course taking place during the second week of November, approximately a week after the King George’s Own Sappers and Miners established their first bomb factory and a couple of months before bomber training schools became established in other divisions of the BEF.

Given the range of essential responsibilities placed upon the sappers of the Field Companies, one cannot but admire the organisational ability of the Company Commanders to free up men from other duties to create a Divisional workshop that responded to the infantry’s demands for the myriad of items of equipment that were important to retain the fighting ability of the men in the trenches. This included items of trench furniture, such as wooden boxes to keep equipment clean and dry, wooden platforms to keep sentries out of the mud and water, and the design and manufacture of extemporised weapons.

With the reorganisation of the Sappers and Miners, Lieut.-Colonel Philip Twining, Commander, Divisional Engineers, 7th (Meerut) Division, proposed to concentrate the division’s bomb making activities in a specific workshop capable of meeting the Corps’ demands for extemporised munitions.

He withdrew seven of the most experienced bomb makers from No 3 Company Sappers and Miners under the command of L/Naik Surgid Akban, along with an NCO and eight privates from the Black Watch with appropriate craft skills, all under the command of Captain Fleming of the 41st Dogras. Their first task was to build a workshop and store for high explosives, and to create an efficient supply chain with local suppliers to provide wire, nails, wood, and other essential materials. By the time the Sappers and Miners from No. 3 Company returned to trench duties on December 3rd, grenade production exceeded 100 a day. By December 6th, the output of the hairbrush grenade, the preferred pattern, had surpassed 300 units a day. But the crisis was looming. On December 13th, Captain Fleming and the men from the Black Watch were ordered to return to their battalions, where they were urgently required. This practically brought grenade production to a halt, and the only saving grace was that the abominable wet weather was affecting the Germans just as much as the BEF, and with troops on both sides devoting themselves to preventing their trenches from collapsing, fighting practically stopped for several weeks, reducing the demand for grenades.

The withdrawal of the soldiers from the Black Watch made it essential to find an alternative workforce if the bomb factory was to continue. The workshop at Gore was within enemy artillery range, far from ideal location a bomb factory, and precluded the employment of civilian labour so Lieut.-Colonel Twinning searched for a new location where he could develop a properly organised bomb factory outside the range of the enemy artillery. He leased a rundown engineering workshop at 78 Rue de Lille, Bethune, complete with a small foundry and woodyard. By December 18th the new workshop was producing mortars, ammunition and grenades, production of the later split between the Bethune factory and a smaller workshop maintained by the Sappers and Miners close to the front that produced 300 grenades a day, leaving the factory to produce the 200 required to make up the Divisional demand for 500 grenades a day.[1]

The workshop made a significant contribution to the local economy, employing several hundred French to civilians, mostly women and girls, who made the moulds for casting the grenade bodies and filled grenades and mortar bombs with high explosives. In addition to making extensive purchases of materials from local suppliers the workshop sub-contracted the manufacture of non-munition items, such as the manufacture of trench furniture, to local French workshops or directly to the population such as sewing sandbags. Eventually, the workshop relieved the pressure on the Divisional Ammunition Column by taking over the storage and issue of standard items of equipment for trench warfare, such as metal loophole plates, sandbags, and bombs for the Woolwich-produced 4-inch and 3.7-inch trench mortars

[1] TNA: WO95/3935: Commander Divisional Engineers HQ. 7th (Meerut) Division. War Diary, December 1914