Ghost Graves on the Somme

Ghost Graves on the Somme. This article identifies five ghost graves to Cornish tunnellers who were killed in an underground explosion and their bodies were not recovered. Nine tunnellers died in this explosion and nine graves were prepared, each complete with a named grave marker. However, five graves were empty creating cenotaphs to act as a place of memorial and place of remembrance for their missing comrades.

On 12 November 1915, the 183rd Tunnelling Company moved to the area around Fricourt in the Somme valley. This area of the Front Line was new to the British, who began the herculean task of building up the resources required for the large offensive planned, in conjunction with the French, for the early summer of 1916—the Battle of the Somme.

The task of the 183rd Company was to drive galleries under the German positions opposite, some of which were defensive, preventing the German Tunnellers from digging under the British positions by blowing underground mines known as camouflets to destroy their diggings. Other galleries were to be offensive, dug under the German positions to be stuffed with high explosives to blow up German trenches and strong points when the time came for the army to attack. During November, the Company was engaged in defensive mining about 70 feet under No Man’s Land, listening for German mining activity. On 20 November, they heard them working for the first time, about 80 feet deep, driving between two of their galleries, known as R1 and R2. As the German digging progressed towards the British lines, it was decided to stop them by blowing four camouflets, each of 1,500 lbs Ammonol, two in R1 and two in R2. They were blown at 3.20 pm on 1 December, and after the poisonous gases from the explosion had dispersed, Lieutenant Twite and some of his Section of Cornish miners went underground to assess the result. At about 7.30, Twite climbed up shaft R10 and went into a dugout at the entrance to write his report. At 8 pm, the Germans retaliated by blowing a large camouflet in front of shafts R32 and R311.

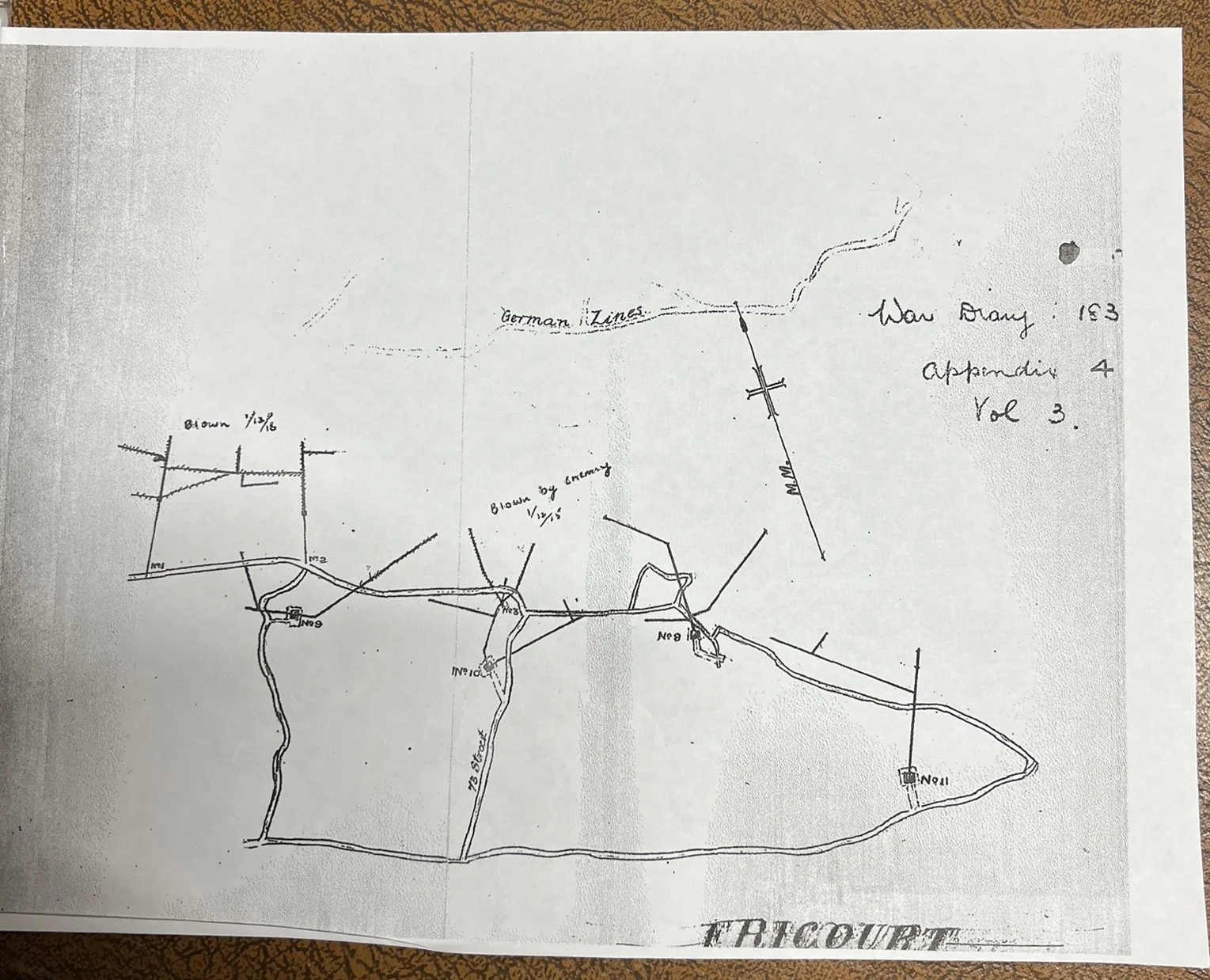

Sketch of the Tunnelling system Fricourt, December 1915.

Of Lieutenant Twite’s men, five were crushed by the collapse of the galleries, both of which were completely destroyed, and two others were asphyxiated trying to escape, probably by toxic gases released from the shattered chalk. At the top of shaft 10 the earth tremors resulting from the explosion caused the roof of the dugout to collapse killing Lieutenant Twite and the two men with him instantly. The following day, 2 December, while clearing up and recovering the bodies, one more Cornish miner died, asphyxiated in a tunnel previously declared free of gas.

Lieut. Twite’s watch, covered in mud and indicating the time of his death. Photograph: With permission of the Trustees of the St Agnes Museum, St Agnes, Cornwall.

The Ghost Graves. Burial & Reburial. Lieut. Twite and the other casualties were buried in a small military cemetery about two and a quarter mile south of Bray sur Somme on the road to Fricourt, about 200 yards east of the road. (Map Ref. 62d.F.17. a. 1.7. – the site can be identified on Trench Mapper on the WFA Website)

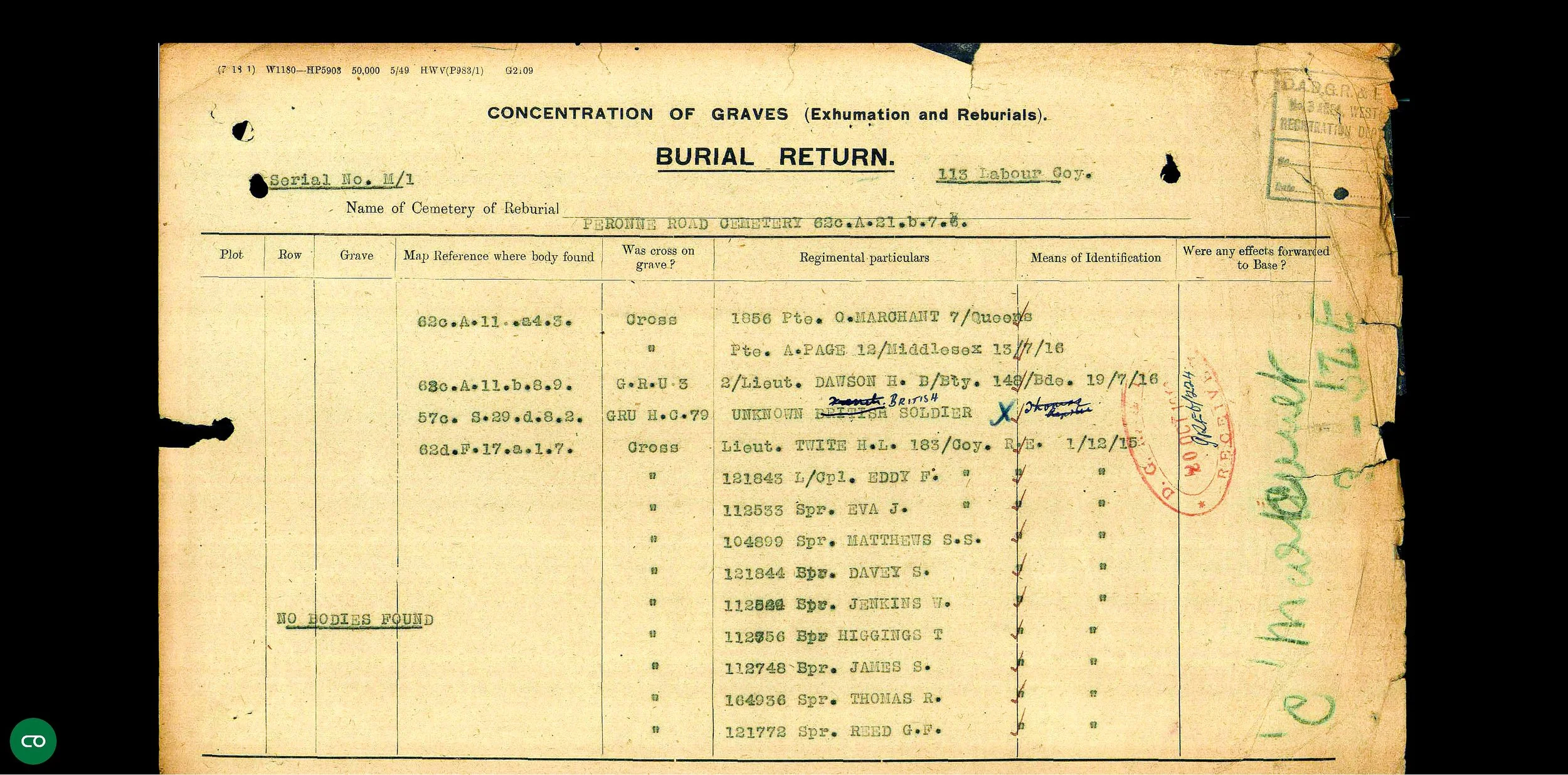

When the bodies were exhumed for reburial at the end of the war we encounter something of a mystery. The Concentration of Graves (Exhumation and Reburial) Return records the graves of Lieut. Twite, L/Cpl Eddy, and Sappers Eva, Mathews, Davey, Jenkin, Higgins, James, Thomas and Reed, were all marked with a cross bearing name, rank, number, unit and date of death.

Burial Returns of exhumations from graves located at map reference 62d.F.17.a.1.7. Ref: Sapper G L Matthews War Casualty Details 546740 CWGC.

When the 113 Labour Company came to exhume the graves, they found that five contained no bodies. The remains of Lieut. Twite, L/Cpl Eddy and Sappers Eva, Eddy, Matthew, along with Sapper Kent, gassed on 2nd December, were recovered and reburied in Citadel New Cemetery, Fricourt.

The graves of Sappers Reed, Davey, Higgins, James and Thomas were empty which suggests that these are the five men who were killed when the deep galleries collapsed and that it was not possible to recover their bodies without clearing the tunnels. These five soldiers join the long list of casualties that have no known grave. Sappers Reed, Davey, Higgins and James are commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial, and, for some reason, Sapper Thomas is commemorated on the Ploegstreet Memorial, a long way from the Somme where he was killed.

That there were no bodies in the original graves is an example of ‘Ghost Graves’ where an empty grave is prepared as an act of commemoration to remember a comrade whose body could not be recovered. (See Tom Tulloch-Marshall No Bodies Found. ‘Ghost’ burials of the Western Front’. Stand To. No. 128, October 2022).

Ghost Graves on the Somme?

This post describes the empty graves, or cenotaphs, in a battlefield cemetery on the Somme constructed by their comrades to comemmorate and remember five Cornish Tunnellers who were killed in an underground explosion that collapsed the deep gallaries where they were working so their bodies were never recovered.

On 12 November 1915, the 183rd Tunnelling Company moved to the area around Fricourt in the Somme valley. This area of the Front Line was new to the British, who began the herculean task of building up the resources required for the large offensive planned, in conjunction with the French, for the early summer of 1916—the Battle of the Somme.

The task of the 183rd Company was to drive galleries under the German positions opposite, some of which were defensive, preventing the German Tunnellers from digging under the British positions by blowing underground mines known as camouflets to destroy their diggings. Other galleries were to be offensive, dug under the German positions to be stuffed with high explosives to blow up German trenches and strong points when the time came for the army to attack. During November, the Company was engaged in defensive mining about 70 feet under No Man’s Land, listening for German mining activity. On 20 November, they heard them working for the first time, about 80 feet deep, driving between two of their galleries, known as R1 and R2. As the German digging progressed towards the British lines, it was decided to stop them by blowing four camouflets, each of 1,500 lbs Ammonol, two in R1 and two in R2. They were blown at 3.20 pm on 1 December, and after the poisonous gases from the explosion had dispersed, Lieutenant Twite and some of his Section of Cornish miners went underground to assess the result. At about 7.30, Twite climbed up shaft R10 and went into a dugout at the entrance to write his report. At 8 pm, the Germans retaliated by blowing a large camouflet in front of shafts R32 and R311.

Sketch of the Tunnelling system Fricourt, December 1915.

Of Lieutenant Twite’s men, five were crushed by the collapse of the galleries, both of which were completely destroyed, and two others were asphyxiated trying to escape, probably by toxic gases released from the shattered chalk. At the top of shaft 10 the earth tremors resulting from the explosion caused the roof of the dugout to collapse killing Lieutenant Twite and the two men with him instantly. The following day, 2 December, while clearing up and recovering the bodies, one more Cornish miner died, asphyxiated in a tunnel previously declared free of gas.

Lieut. Twite’s watch, covered in mud and indicating the time of his death. Photograph: With permission of the Trustees of the St Agnes Museum, St Agnes, Cornwall.

The Ghost Graves. Burial & Reburial. Lieut. Twite and the other casualties were buried in a small military cemetery about two and a quarter mile south of Bray sur Somme on the road to Fricourt, about 200 yards east of the road. (Map Ref. 62d.F.17. a. 1.7. – the site can be identified on Trench Mapper on the WFA Website)

When the bodies were exhumed for reburial at the end of the war we encounter something of a mystery. The Concentration of Graves (Exhumation and Reburial) Return records the graves of Lieut. Twite, L/Cpl Eddy, and Sappers Eva, Mathews, Davey, Jenkin, Higgins, James, Thomas and Reed, were all marked with a cross bearing name, rank, number, unit and date of death.

Burial Returns of exhumations from graves located at map reference 62d.F.17.a.1.7. Ref: Sapper G L Matthews War Casualty Details 546740 CWGC.

When the 113 Labour Company came to exhume the graves, they found that five contained no bodies. The remains of Lieut. Twite, L/Cpl Eddy and Sappers Eva, Eddy, Matthew, along with Sapper Kent, gassed on 2nd December, were recovered and reburied in Citadel New Cemetery, Fricourt.

The graves of Sappers Reed, Davey, Higgins, James and Thomas were empty which suggests that these are the five men who were killed when the deep galleries collapsed and that it was not possible to recover their bodies without clearing the tunnels. These five soldiers join the long list of casualties that have no known grave. Sappers Reed, Davey, Higgins and James are commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial, and, for some reason, Sapper Thomas is commemorated on the Ploegstreet Memorial, a long way from the Somme where he was killed.

That there were no bodies in the original graves is an example of ‘Ghost Graves’ where an empty grave is prepared as an act of commemoration to remember a comrade whose body could not be recovered. (See Tom Tulloch-Marshall No Bodies Found. ‘Ghost’ burials of the Western Front’. Stand To. No. 128, October 2022).

Annie E Allen. V.A.D.

Annie Allen V.A.D. commemorated on Ecclehall War Memorial

Eccleshall War Memorial.

As a student of the First World War, I am always interested in the names of the individuals commemorated on war memorials, and it is my custom to read them aloud as an act of remembrance. When I first saw the Eccleshall memorial in Staffordshire, I was surprised to see that the first name inscribed on it was that of a woman, Anne E. Allen VAD, and I immediately wanted to find out more about her. Who was she? Why was a VAD so commemorated? Did she die on active service?

Voluntary Aid Detachments. (VAD). In 1906, as part of the reorganisation of the army and the creation of the Territorial Force, the War Office developed a scheme through which the British Red Cross and the Order of St John of Jerusalem could provide supplementary aid to the Territorial Forces Medical Services. These units were called Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs), but soon after their formation, the initials VAD started to be used as a nickname to describe the members of the units rather than the unit itself, and the name stuck. Today, these Voluntary Aid Detachments are predominantly viewed as female organisations, and while most members were women, it is also important to remember that many men served, providing essential and valuable services, such as ambulance driving. To become a VAD, a woman had to achieve certification in first aid and home nursing, whereas male VADs only had to obtain a first aid certificate.

The first VADs mainly were upper and middle class women who wanted to do some voluntary work, usually associated with their local hospitals, within a respectable and socially acceptable framework but during the war their role expanded and becoming a VAD was the route by which many sheltered young women swapped the certainties of an Edwardian drawing room for hospital wards full of the mutilated and wounded from the battlefields. Two VADs who became famous in later life, but remained marked by such experiences, were Vera Brittain and Agatha Christie.

World War One. By November 1914, the unexpectedly high casualties had convinced the government that the standard three-year nursing course was insufficient to provide the number of nurses required, and they turned to the voluntary sector. By early 1915, the Joint War Committee of the Red Cross and St John’s had recruited, trained and certificated hundreds of VADs who were to play an essential role in the provision of medical services to wounded servicemen. For VADs serving at home, their most important contribution was raising funds and then providing staff for the dozens, if not hundreds, of auxiliary and convalescent hospitals set up in hotels and country houses to meet the needs of the recovering wounded. Some VADs, usually through family influence, served in the war zones and acted as ward clerks, dressers, etc, to the trained nurses dealing with severe casualties in the forward casualty clearing hospitals.

Eccleshall VAD nurses taken at Trentham Gardens, date unknown. These VADs may have been attached to the small VAD convalescent hospital in Eccleshall, and not the larger Sandon Hospital where Annie Allen served.

Who was Annie Allen? Annie Elizabeth Allen, the 3rd daughter of William Allen, vicar of Eccleshall, 1883-1915 and Prebendary of Sandiacre in the Cathedral of Lichfield. Annie was born on February 5 1872, and was educated at home, but, due to ill health, spent much of her early life abroad. When at home, as far as her health permitted, she was an enthusiastic assistant in her father’s parochial work, and her contributions were widely recognised in the reports of local ‘goings–on’ that appeared in the Staffordshire Advertiser and Staffordshire Chronicle of the period. For example, we find that, with the rest of her family, she helped to raise the funds required to build the new church at Slindon and at the party organised for the villagers after the service of dedication on October 15 1894, the Staffordshire Advertiser noted that Miss A.E. Allen was one of the people who sang at the entertainment.

When war broke out, Annie joined the Red Cross, becoming a VAD. In September 1915, Sandon Hall opened as a Military Convalescent Hospital run by the Sandon and Eccleshall Red Cross, and Annie joined the staff, rising through the ranks to become one of the two Quartermasters.

Sandon Hall, the ancestral home of the Harrowby family. An auxiliary military hospital and Reception Centre in both World Wars.

In her obituary, the Staffordshire Advertiser noted that she was very happy in this work, highly popular with staff and patients, and that during this period, her health had greatly improved. We also know from the local newspapers something of what Annie was doing in the last two weeks of her life. The Advertiser for January 4 1919, reported her involvement in an evening of entertainment held in Eccleshall attended by soldiers from the VAD Red Cross Hospital. On the 18th, the Chronicle carried a report of a supper, followed by presentations and a fancy dress ball, to mark the closure of the Sandon VAD hospital. On this occasion, the Commandant, Miss Parker-Jervis CBE, was presented with a large silver mirror by the officers and sisters past and present, while the VADs, some eighty-four in number, who had worked at the hospital, presented her with a beautiful Red Cross. In her reply, Miss Parker-Jervis said that she had spent some of the happiest years of her life at Sandon and knew that she had the best staff any hospital ever had. Quartermaster Caudler was presented with a pair of silver candlesticks, Quartermaster Allen with a silver frame and Sister Dean with a silver brush, comb and mirror. After the presentations, the dancing commenced, which, as the Advertiser notes, continued until a late hour.

Her Death. Sadly, her next appearance in print is the notification of her death on January 20, 1919, at Sandon Hall Auxiliary Red Cross Hospital. The cause of death was a sudden attack of severe laryngitis, but whether this diagnosis is accurate, we will never know. Young persons sent abroad for their health in late Victorian England usually had a history of respiratory disease. She may have had severe asthma or less likely consumption (tuberculosis), but early 1919 was also the time of the great flu pandemic in Staffordshire, as witnessed by the number of young New Zealanders who lie in the British Military Cemetery on Cannock Chase, and she may have also been a victim.

The Funeral. Annie Allen's funeral was a major event reported in great detail by the press. Her body was brought from Sandon Hall on the afternoon of Wednesday 22nd January to Holy Trinity Church, Eccleshall, the route lined by a large silent crowd. The coffin was place in the aisle where hundreds filed past the flag-draped coffin flanked with an honour guard of VAD nurses. The funeral next day was officiated by no less than four members of the clergy, and the church was packed to overflowing with family, friends and detachments of VADs so that the crowds spilled out to fill the churchyard from where they took part in the singing of the hymns. As the coffin was lowered into the grave the last post was sounded and a Company from the Nottingham and Derby Regiment fired volleys over the grave. There were so many beautiful wreaths that they totally covered the grave and surrounding area.

Annie’s grave is to the left of the church door, next to that of her parents. Unfortunately, the lettering on the stone surround has faded with time, but it is just possible to identify her when the light falls on the faded lettering.

Annie Allen was obviously widely liked and respected throughout the Parish of Eccleshall and the surrounding area, and her funeral, with its military overtones, is quite exceptional for a civilian, even if she was a VAD. Perhaps the sudden death of one so beloved within the community served as a focus for the grief for those who would never return from what, in British terms, remains The Great War of 1914-1918. She is commemorated on the Eccleshall War Memorial, dedicated by the Bishop of Lichfield and the Earl of Dartmouth, the Lord Lieutenant of Staffordshire on September 26 1921, and on the Nurses Memorial in the National Memorial Arboretum dedicated to VADs and Professional Nurses who lost their lives in both world wars.

The Great War Dead of Ecclehall, Staffordshire.

The Nurses Memorial.