Ghost Graves on the Somme

On 12 November 1915, the 183rd Tunnelling Company moved to the area around Fricourt in the Somme valley. This area of the Front Line was new to the British, who began the herculean task of building up the resources required for the large offensive planned, in conjunction with the French, for the early summer of 1916—the Battle of the Somme.

The task of the 183rd Company was to drive galleries under the German positions opposite, some of which were defensive, preventing the German Tunnellers from digging under the British positions by blowing underground mines known as camouflets to destroy their diggings. Other galleries were to be offensive, dug under the German positions to be stuffed with high explosives to blow up German trenches and strong points when the time came for the army to attack. During November, the Company was engaged in defensive mining about 70 feet under No Man’s Land, listening for German mining activity. On 20 November, they heard them working for the first time, about 80 feet deep, driving between two of their galleries, known as R1 and R2. As the German digging progressed towards the British lines, it was decided to stop them by blowing four camouflets, each of 1,500 lbs Ammonol, two in R1 and two in R2. They were blown at 3.20 pm on 1 December, and after the poisonous gases from the explosion had dispersed, Lieutenant Twite and some of his Section of Cornish miners went underground to assess the result. At about 7.30, Twite climbed up shaft R10 and went into a dugout at the entrance to write his report. At 8 pm, the Germans retaliated by blowing a large camouflet in front of shafts R32 and R311.

Sketch of the Tunnelling system Fricourt, December 1915.

Of Lieutenant Twite’s men, five were crushed by the collapse of the galleries, both of which were completely destroyed, and two others were asphyxiated trying to escape, probably by toxic gases released from the shattered chalk. At the top of shaft 10 the earth tremors resulting from the explosion caused the roof of the dugout to collapse killing Lieutenant Twite and the two men with him instantly. The following day, 2 December, while clearing up and recovering the bodies, one more Cornish miner died, asphyxiated in a tunnel previously declared free of gas.

Lieut. Twite’s watch, covered in mud and indicating the time of his death. Photograph: With permission of the Trustees of the St Agnes Museum, St Agnes, Cornwall.

The Ghost Graves. Burial & Reburial. Lieut. Twite and the other casualties were buried in a small military cemetery about two and a quarter mile south of Bray sur Somme on the road to Fricourt, about 200 yards east of the road. (Map Ref. 62d.F.17. a. 1.7. – the site can be identified on Trench Mapper on the WFA Website)

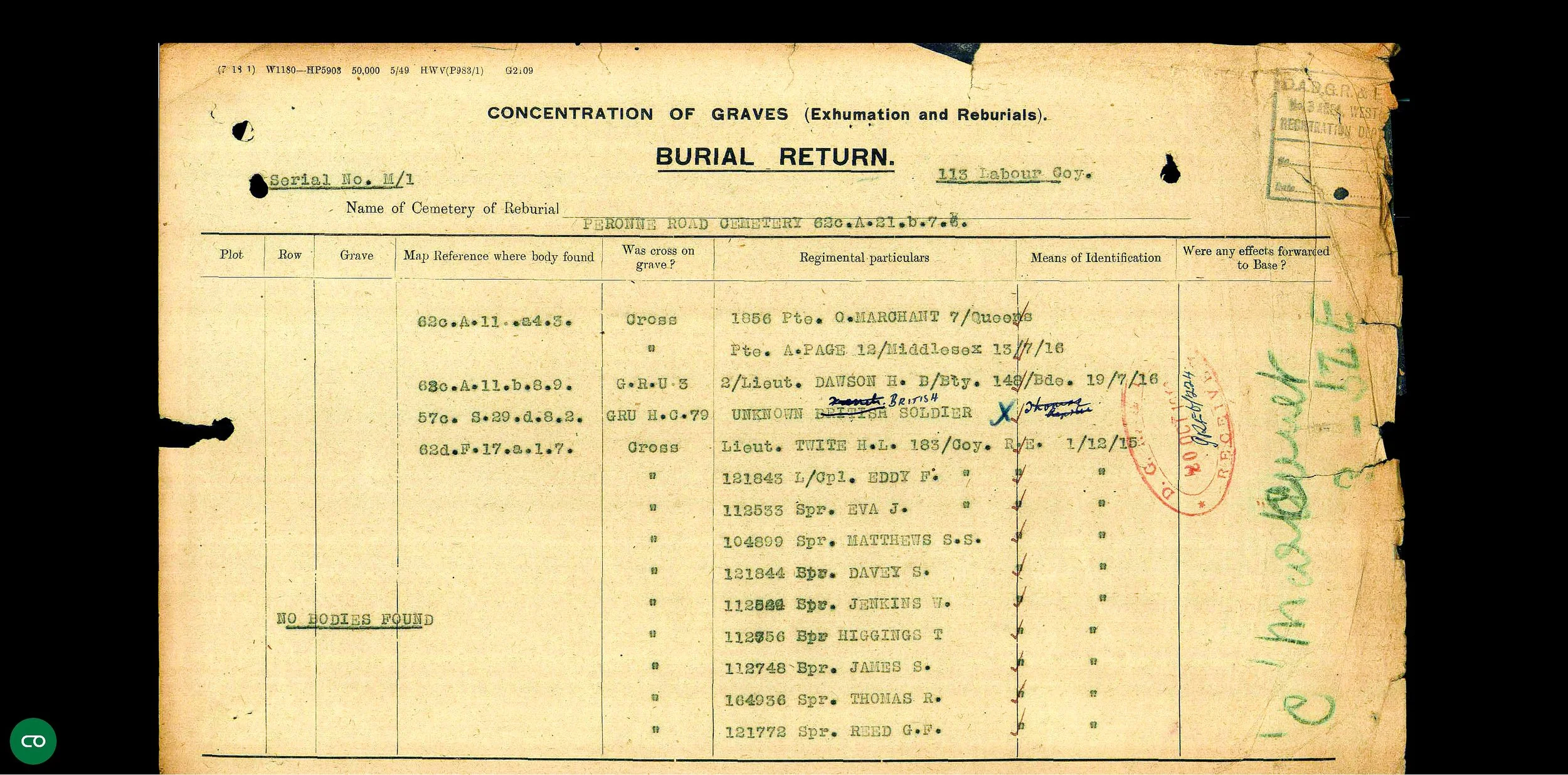

When the bodies were exhumed for reburial at the end of the war we encounter something of a mystery. The Concentration of Graves (Exhumation and Reburial) Return records the graves of Lieut. Twite, L/Cpl Eddy, and Sappers Eva, Mathews, Davey, Jenkin, Higgins, James, Thomas and Reed, were all marked with a cross bearing name, rank, number, unit and date of death.

Burial Returns of exhumations from graves located at map reference 62d.F.17.a.1.7. Ref: Sapper G L Matthews War Casualty Details 546740 CWGC.

When the 113 Labour Company came to exhume the graves, they found that five contained no bodies. The remains of Lieut. Twite, L/Cpl Eddy and Sappers Eva, Eddy, Matthew, along with Sapper Kent, gassed on 2nd December, were recovered and reburied in Citadel New Cemetery, Fricourt.

The graves of Sappers Reed, Davey, Higgins, James and Thomas were empty which suggests that these are the five men who were killed when the deep galleries collapsed and that it was not possible to recover their bodies without clearing the tunnels. These five soldiers join the long list of casualties that have no known grave. Sappers Reed, Davey, Higgins and James are commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial, and, for some reason, Sapper Thomas is commemorated on the Ploegstreet Memorial, a long way from the Somme where he was killed.

That there were no bodies in the original graves is an example of ‘Ghost Graves’ where an empty grave is prepared as an act of commemoration to remember a comrade whose body could not be recovered. (See Tom Tulloch-Marshall No Bodies Found. ‘Ghost’ burials of the Western Front’. Stand To. No. 128, October 2022).