CHAPTER 1.

The Manufacture of Extemporised Munitions by the BEF in 1914.

Extemporised Munitions.

The manufacture and use of extemporised munitions is as old as warfare itself. In the context of this article, it refers to items of equipment designed and manufactured outside the normal supply chain by the troops of an army engaged in warfare.

It is probably a truism to state that the most common attitude towards extemporised weapons is one of bemused disbelief that such makeshift bits of kit, which have acquired a reputation for being more dangerous to the user than the enemy, were employed in warfare. However, I hope to go some way towards modifying this view and demonstrate that, although far from perfect, these munitions were a crucial first step towards overcoming the enemy's defensive firepower.

Almost by definition, the design of extemporised munitions had to be as simple as possible, capable of construction using whatever materials were available locally, using the simplest of tools, as Field Companies on campaign were not issued with the type of machinery found in any small engineering workshop such as lathes, drills or metal working equipment, and even if such equipment could be purchased, or hired, locally it is unlikely than any of the sappers were skilled in their use.. Out of necessity they produced munitions that were, by any engineering standards, rough and ready, yet still capable of striking a balance between safety and combat effectiveness. Such weapons are light years away from the high-quality materials and fine engineering tolerances deemed necessary by the conventional munitions industry to produce a safe and effective weapon. However, when it came to the manufacture of more complex munitions, such as mortar bombs, the Royal Engineer bomb factories would sub-contract most of the skilled work to local French engineering workshops. This is also the place to put to bed one of the enduring myths about extemporised munitions: that they were manufactured by infantry idling away their spare time while sitting in the depths of their trench. In contrast, all surviving reports on the manufacture of trench stores, including munitions, demonstrate that they were manufactured in designated workshops or factories under the control of the Royal Engineers. The manufacturer of explosive munitions requires knowledge and experience in handling explosives and detonators, which means the Royal Engineers and not untrained infantry. The origin of the myth may lie in the fact that, for safety reasons, the detonators and fuses were packed separately in the boxes of grenades delivered to the trenches, and required insertion before the grenade became active, a task carried out in the trenches, normally by that trained infantry that formed the battalion bombing squad.

Another widespread belief is that improvised weapons were ineffectual and intrinsically dangerous, but if we set aside soldiers' tales in post-war reminiscences, and look at, albeit scarce, contemporary evidence from War Diaries, we find that, on the whole, extemporised weapons were generally effective in doing what was expected of them, After all a few ounces of high explosive will do a lot of damage to an unprotected infantryman whether it is delivered in a tin can full of scrap iron, or in a shiny new Mills grenade. The question is not whether extemporised munitions were effective, but whether they were reliable, and here, the odds are stacked against them. This is best explained by looking at the construction of the jam tin hand grenade. The instructions for manufacture in the Official History are as follows,

Take a tin jam pot, fill it with shredded gun cotton and ten-penny nails, mix according to taste. Insert a No. 8 detonator and a short length of Bickford’s fuse. Clay up the lid. Light with a match, pipe, cigar, or cigarette, and throw for all you are worth.[1]

[1] Official History 1915 (i), p.7

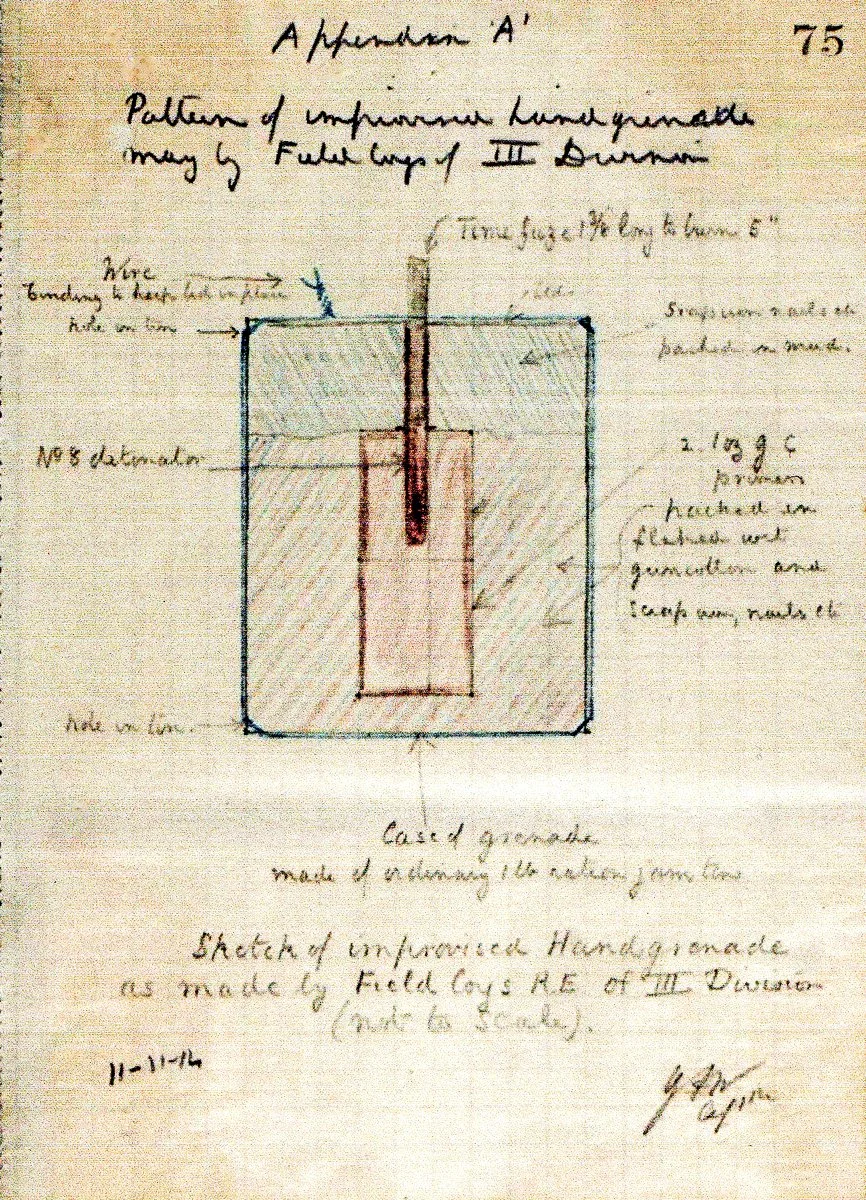

Diagram of a jam tin hand grenade. November 1914. TNA WO95/1397. War Diary. 3rd Division. Commander Royal Engineers. November 1914, Appendix A

Here we have a weapon assembled from three or four simple components. The casing is the ubiquitous empty ration tin used upside-down so that the base of the tin is the top of the grenade. This is filled with bits of scrap iron mixed with flaked guncotton, which, as it spontaneously explodes if it dries out, is kept damp by being packed in wet clay or thick mud, the open end of the tin closed with a wooden plug. The main charge of flaked guncotton is detonated by a small solid guncotton primer buried within the mixture and attached to a Nobel No. 8 commercial detonator, thousands of which were available from the mining district around Bethune. The free end of the detonator was attached to a short length of Bickford safety fuse with a 5-second burn time. To prevent the fuse from falling out when the grenade was thrown or hit the ground, it was held in place by a length of thin wire soldered to the tin.

In the earliest grenades, the free end of the fuse was exposed and lit by an open flame from a match, pipe, or cigarette but later the Field Companies obtained commercially assembled Bickford fuses in which the top of the fuse was coated with a fuze consisting of an ignition mixture almost identical to the red coloured material used for the head of non-safety matches and protected from damp by a wax-paper cap.[1] It was this ignition system, particularly the fuse-detonator interface, that was the great weakness in all extemporised explosive munitions and was responsible for their poor reliability and most accidents. Once the fuse was lit, the grenade was thrown, and five seconds later it exploded. What could go wrong with such a simple mechanism? The answer was plenty. Bickford fuses were notoriously susceptible to damp, making them difficult, if not impossible, to light. The most common grenade failure was the fuse becoming detached from the detonator, either during the throw or when the grenade hit an object at the end of its throw.

When the BEF went to war in August 1914, it was neither trained nor equipped for trench warfare. It possessed no trench mortars and only a token number of the No. 1 percussion hand grenade, which, at this stage of the war, was not an infantry weapon but the prerogative of specially trained Royal Engineers. The earliest mention of extemporised hand grenades I have identified is an entry in the War Diary of the Commander, Royal Engineers 1st Division for September 29th 1914, the Battle of the Aisne. It had been reported that the enemy was digging a new trench towards the line held by the 2nd Infantry Brigade and the 23rd Field Company. The 23rd Field Company, RE, was ordered to sap out towards the offending trench and attack it with grenades. Apparently, there were no No. 1 percussion grenades available and, as a substitute, the Royal Engineers were instructed to manufacture a few and, if they were successful, supply them to the 2nd Infantry Brigade. There are also brief entries in the Royal Engineer War Diaries that the 3rd Division manufactured about 10 jam-tin grenades for the Northumberland Fusiliers’ attack on the stable block at Herenthage Chateau on November 15th, and also when the BEF was relieved by the French after First Ypres and went into reserve a number of the Field Companies started experimenting with the manufacture of grenades in anticipation of their return to the trenches.

[1] To eliminate confusion, FUZE is not the American spelling of FUSE, for they are two distinct nouns describing two distinct functions. A FUZE is a device for initiating the explosion of high explosives in artillery shells, mortar bombs, grenades, etc., and, for this discussion, the FUZE of the Brock lighter is the match-head mixture. The FUSE is the device for transmitting the fire and is a short length of Bickford safety fuse connecting the match-head mixture with the detonator.