Second Army Workshop. Bethune.

The evolution of the Second Army workshops developed in two phases. On 21 November 1914, after the First Battle of Ypres, the 3rd Division withdrew into reserve to recuperate, retrain, and absorb its reinforcements. During this period, its Field Companies began manufacturing jam pot grenades and instructing selected infantry in their use. There is no evidence that the Division developed a specific workshop to oversee this activity, as the Division was out of the line. The demand for grenades, both dummy and live, was geared to infantry bomber training rather than to attacking the enemy. While there is no evidence that the 3rd Division attempted to produce trench mortars, they did show an interest in alternative methods of projecting grenades by building and experimenting with a ballista, a type of siege catapult.[1] After November, all mentions of grenade manufacture and the training of infantry disappear from the War Diaries, but these activities continued, as reports attached to the Commander Royal Engineer’s War Diary for January 1915 are on different types of fuze lighters for grenades and an evaluation of the first batch of the double cylinder grenade received by the Division.

The experience gained with the mortars lent by Sir Douglas Haig for the attack at Wytschaete was the trigger for the 3rd Division to produce its own. When Lieutenant Denning returned the surviving mortar to the 1st Division’s workshop at Bailleul, he took with him several sappers and some steel tubing to manufacture his own trench mortars; this marked the beginning of what would become the first of the II Corps’ bomb factories. Later, when the 1st Division workshop moved to Bethune in late December, Lieutenant Denning took over the Bailleul factory along with its civilian labour. However, the factory's output was never large, as it was poorly equipped with the necessary machinery. Furthermore, without any industrial towns nearby, sourcing supplies, such as metal pipes for the mortar barrels, was difficult. By January 3rd, 1915, it had delivered only 3 mortars, 75 bombs, and 40 trench boxes to the 3rd Division. After receiving a further supply of boiler tubing, they managed to add 3 additional mortars by late February. On January 9th, the 3rd Division received its first 3.7-inch ML trench mortar from Woolwich. From that point on, at least until April, the bomb factory at Bailleul ran the Woolwich mortars alongside their extemporised models. In March, they received the latest update to the 3.7-inch, which used guncotton as a smokeless propellant and was fired by a modified trigger mechanism of the .303 service rifle. This was judged a great success and considered superior to anything they could make themselves.[2] I could find no evidence that indicates when this workshop stopped production.

Second Army Workshops (Newton).

The next phase in the development of the 2nd Army Workshops, and one that was destined to become the largest and most successful operation run by the Royal Engineers on the Western Front, was created, not by the Royal Engineers, but by a Territorial infantry officer, Henry Newton.

Captain Henry Newton, 1/5 Battalion Notts & Derby Regt. (Sherwood Foresters) T.F.

In civilian life, Newton was a director in the family electrical engineering company, Newton Brothers, based in Derby. Professionally, Newton described himself as an electrical engineer, but his responsibilities within the Company were in production and the non-electrical sides of the business. A keen supporter of the Territorial Army, he was, by April 1915, in France, a Captain, and Company Commander, with the 1/5 Battalion Sherwood Foresters (T.F.). When out of line, Captain Newton, with some of the men of his own Company, probably employees of the family firm, passed their time working in an abandoned blacksmith shop in Kemmel, making gadgets, such as rifle batteries, that would be useful to his battalion in the trenches.[3]

This activity brought him to the attention of Major-General W.T. Furse, Senior Staff Officer in II Corps, who ordered him to establish a workshop to provide similar items for all of II Corps, not just one battalion. Newton was extremely fortunate in finding an engineering school in Armentiéres, the École Nationale, that was fully equipped with engineering, woodworking, sheet and hot metal workshops, and with its own steam power plant and a small furnace and forge for working metals, which had been abandoned by staff and pupils as it was within range of enemy heavy artillery. This was taken over by II Corps and, on May 12th 1915, Captain Newton, accompanied by 45 tradesmen drawn from the infantry of the 46th Division, one suspects the majority from Newton Brothers, took over the school, and came under the control of the Commander, Royal Engineers Second Army.[4]

Aware of the inconsistencies in the design of trench mortars manufactured by the Field Companies, who had to use whatever suitable piping they could lay their hands upon, Newton was determined to turn out products of consistent quality from the start, and he applied the manufacturing practices normally practised by a commercial engineering company in his workshop. For his trench mortars, rather than relying upon existing pipes for his barrels,

He elected to cast his own. This allowed him to control the quality of his mortar tubes and, importantly, the bore size, adopting a 3.7-inch calibre to be compatible with the ammunition provided by the War Office for the Woolwich 3.7-inch trench howitzer, which was just coming into service. With his furnaces, Newton could cast his mortar barrels from cast iron or brass, obtained by melting empty cartridge cases salvaged by the infantry in exchange for a completed mortar. His light trench mortars were very popular, and to meet the high demand, Newton designed and built four additional furnaces, each capable of holding 200 lbs. of molten brass or cast iron.

Working closely with troops in the trenches, Newton received continuous feedback on the performance of his mortars. This drove his interest in discovering the ideal properties of trench mortars under combat conditions. Over the next three years, Newton conducted extensive experimentation with the Research Section at GHQ on mortar and ammunition design. After the Ministry of Munitions was formed in June 1915, his collaborations expanded to the Trench Warfare and Munitions Invention Departments. His work on trench mortars led to improvements in design and functionality for models already in service, such as the 3-inch Stokes and the 2-inch medium trench howitzer.

Staffing.

In addition to high-profile munitions, such as the Pippin rifle grenade, the Second Army workshop, like the First Army workshop in Bethune, was a major producer of other items of equipment. These included trench boxes, periscopes, rifle rests and range blocks for rifle grenades, machine gun mountings, hand carts, and similar items. The manufacturer of many non-munitions items would have been subcontracted to local suppliers. These suppliers also provided the workshop with much of the material it required, such as iron fittings, timber, screws and bolts, and small tools that the army could not or would not supply.[5]

As the number of troops on the Western Front increased throughout 1915, demand on the workshop rose, leading to a crisis in labour availability, both skilled and unskilled. As these bomb factories were unofficial establishments, set up under the authority of the Commander-in-Chief of an army on active service, they did not appear in the BEF's Order of Battle, so there was no mechanism within army regulations to allocate a permanent military staff. We must assume that there was some flexibility in this for Newton; to keep his munitions factory operating, he must have had a permanent core of staff who carried out research and development, trained and supervised the workers, and ensured the factory's operations. In the beginning, most of the workers were probably infantrymen detached from their battalions, like any other Royal Engineer working party, and while it is likely that some of these men became key workers, their skills and expertise were lost when their battalions were rotated out of the operational area.

The answer was to employ civilian workers. When Newton started the workshop, he employed about 20 civilians, rising to over 200 when production of the Pippin grenade began in the summer of 1915, and would increase to almost 1,000 during the Battle of the Somme. We know little about the nature of these workers except that the majority were women and girls who, like their sisters in the munitions factories in Britain, proved to be outstanding in manufacturing the moulds for casting the grenade bodies, filling them with explosives, and packing the completed grenades, rods and detonators into their specially designed boxes.

The Move to Hazebrouck.

In August 1915, after practically ignoring the town for several weeks, German heavy artillery increased its shelling of Armentiéres, which led to suspicions that the Germans may have identified the Workshop, and it was thought prudent to relocate the machinery to Hazebrouck. With the move, the workshop gained more space and access to a wider range of machinery, enabling production expansion. Suitable buildings were converted into fitters, tinsmiths, machinery and carpenter shops, and a new foundry was constructed. Two fields were acquired outside the town for the erection of the magazine to store explosives, along with the small huts where the women and girls filled grenades and bombs. Most civilian workers were transferred from Armentières, but as grenade production expanded, many more were required, and the civilian workforce reached 950 during peak production in 1916.

Records relating to the factory's output have not survived, so we know little about the range and quantities of items produced. By any estimate, it must have been extensive, with the output of Pippin grenades far in excess of anything else manufactured.[6] In its hand grenade form, some 80,000 Pippin grenades were produced before the Mills bomb superseded it in early 1916, but the rifle grenade was its most successful product. This stayed in production until the middle of 1917; the Hazebrouck workshop alone produced over 700,000, reaching a maximum output of 5,000 a day to meet the needs of the Somme battles. It was also manufactured at Merville and at the First Army Workshop in Bethune, and to meet the demand for cast-iron grenade bodies and firing rods, contracts were placed with numerous French foundries, some as far away as Paris.

One cannot over-emphasise the success of Henry Newton as an inventor who had a significant impact on the design and performance of a wide range of munitions and other equipment for trench warfare. His range of inventions probably places him as the foremost inventor during the war, a fact recognised by the American Government, which awarded him a $100,000 prize for his achievements.[7] He did not work alone. There were close collaborations with the Ministry of Munitions, in particular the mortar and grenade sections of the Trench Warfare Supply Department and the Munitions Inventions Department, where interest focused on Newton’s all-terrain tracked vehicle for carrying troops and supplies on the battlefield. These collaborations were supported by the willingness of Second Army GHQ to release Newton from his duties in France to spend periods of time in London. In 1917, the War Office agreed to Newton’s permanent transfer to the Ministry of Munitions. He became a member of the newly established Trench Warfare Committee and, later in the same year, Chief of Design in the Mechanical Traction Department.

Vinette. The Pippin Rifle Grenade.

Probably the most successful product of the Second Army Workshop was the Pippin grenades. Throughout June and July 1915, with light trench mortars still in short supply, Captain Newton set about developing an effective rifle grenade that he could produce in large quantities with the resources at his disposal. The result was the Newton Pippin grenade, available in both hand and rifle configurations.

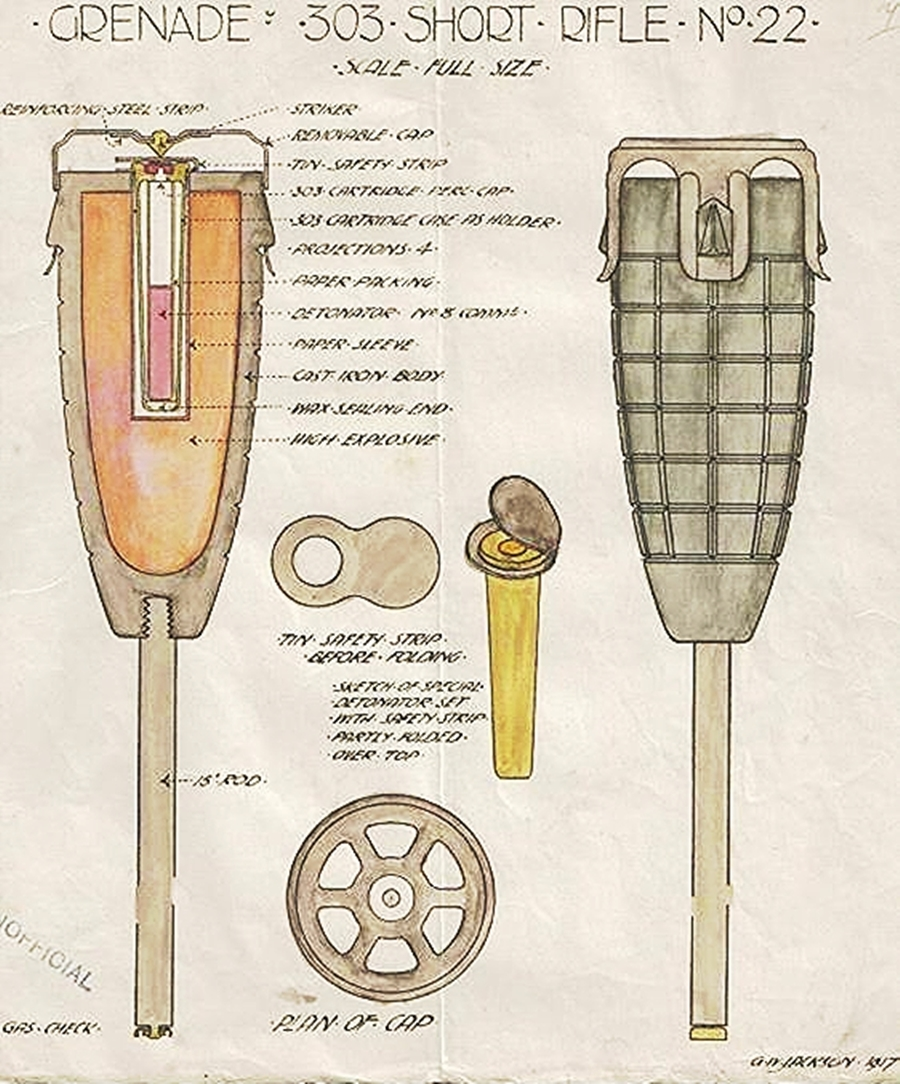

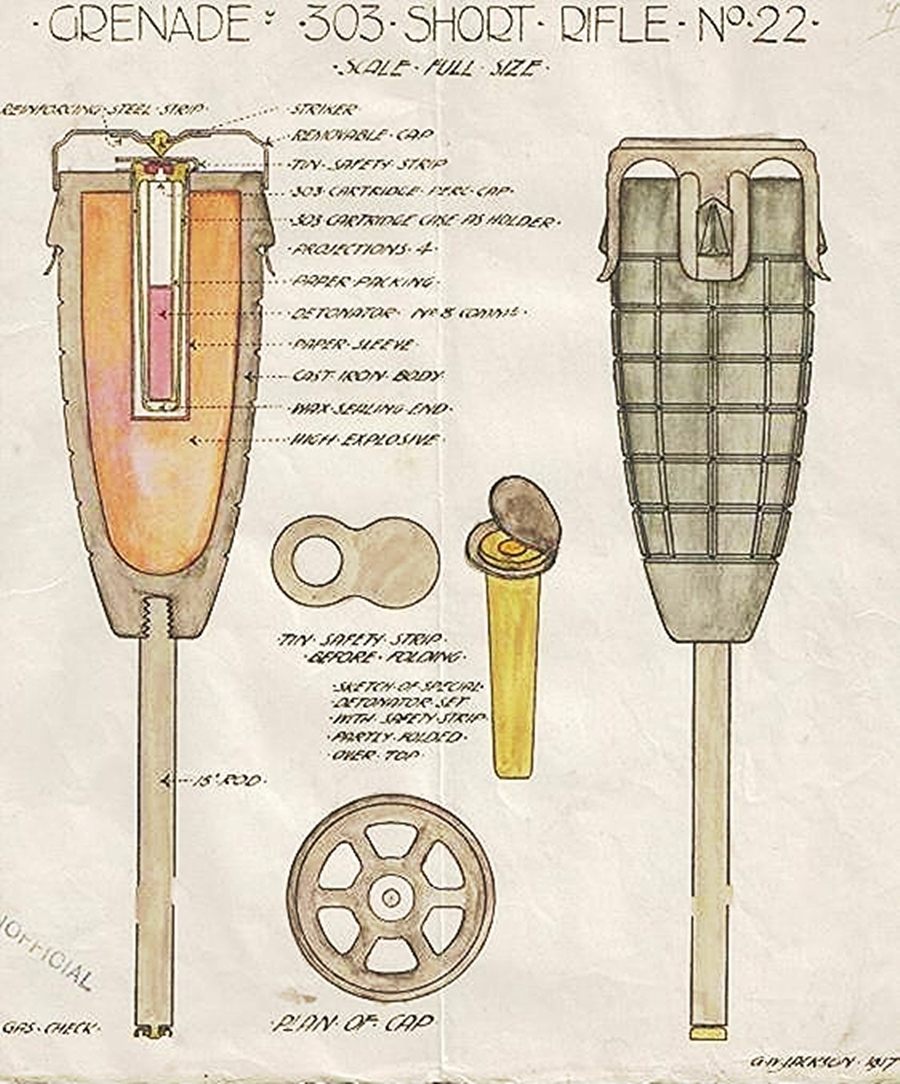

Note: These drawings date from 1917and show the late version of the grenade with the tin safety strip inserted between the tip of the firing pin and the primer of the 0.303 cartridge case.

Made of cast iron, the cone-shaped body was 10 cm long and 4.6 cm at the top, a simple design that was easy to cast and required minimal cleaning-up when removed from the mould. For the rifle grenade, the solid base was drilled to take his short, 15 cm, firing rod that fitted the rifle's barrel, an advantage over the Hales rifle grenade, which required a larger, heavy steel rod that was cumbersome for the rifle grenadier to carry when crossing rough ground. The completed Pippin rifle grenades weighed about 380 grammes (0.85 lbs), of which 64 were their high-explosive charge of ammonal. The rifle grenade was fitted with a percussion fuse housed within its body.

The top of the grenade was covered by a light tin cap with a small steel firing pin soldered underneath. This cap clipped over the top and was held in place by 4 small lugs projecting from the grenade body with the steel firing pin set to engage with the primer of an empty 0.303 rifle cartridge case. Insert it into the cartridge, with the commercial detonator in contact with the primer. protected by a cardboard detonated tube and pushed into the high explosive. This arrangement forms the basis of the Newton Instantaneous, or graze fuse, often claimed by grenade enthusiasts to be a unique invention, but in fact was a well-known method of making a percussion fuse that was used in extemporised grenades produced during the Boer War,[8] and by McClintock for both his rifle and hand grenades.[9] That being said, Newton’s design was superior in that it was better engineered, cheaper, easier to make with semi-skilled labour, and worked under most combat conditions.

The pippin rifle grenade had a maximum range of 400 yards and had several design features that made it superior to the Hales rifle grenade. It was already noted that the short firing rod made it easier to handle when the rifle grenadier was moving over rough ground, when supporting infantry in an attack or trench raid. Newton also fitted a gas check, which was unusual for British rifle grenades of the period. This device, fitted to the base of the firing rod, expanded when the rifle was fired, filling any gaps between the firing rod and the rifle barrel. Such a device was necessary because the firing rods were not a tight fit, and propellant gases could escape through the gap between the rod and the inner barrel wall (known as windage) and along the grooves of the rifling. This led to variable gas pressures, resulting in unpredictable variations in range, but the gas check allowed the pressure to build to a constant level before it collapsed, releasing the rod and discharging the grenade.

Modifications by the Ministry of Munitions.

By February 1916, the Pippin rifle grenade was in extensive and successful service throughout the BEF, with only a small number of reported accidents. Based on this success, the War Office suggested that Captain Newton return to the UK and demonstrate his grenade to the Ministry of Munitions, with a view to its adoption for factory production. When Newton arrived in London with samples of his grenade, the Munitions Invention Department, which was to carry out the assessment, had not finalised the arrangements, and the subsequent delay meant that Newton had to return to France before he could demonstrate his rifle grenade, leaving his samples with the Ministry of Munitions to be test-fired in his absence. With Newton back in France he had little influence over the subsequent fate of his invention, and what happened to the Pippin rifle grenades in the hands of the Ministry provides us with a case study - by no means unique - of what could happen to a successful trench warfare munition, moreover devised by soldiers in contact with the enemy, once it fell into the hands of the experts in the Ordinance Committee and the Munitions Invention Department. Most staff who populated these two organisations were recognised experts in the design and evaluation of equipment issued to the army, and many had transferred from the War Office and were discharging essentially the same responsibilities as they had always done, except now under the banner of the Ministry of Munitions. Unfortunately, as members of the War Office establishment, they had brought into the Ministry set values that acted as a block to the assessment of trench warfare munitions developed by the Trench Warfare Department or the Royal Engineer workshops in France.

Their default position, or mindset, was that only materiél designed and approved by the time-honoured procedures of the War Office was fit to be issued to the army. This negative “not made here” culture could lead to the rejection of perfectly effective munitions devised elsewhere, whether the army workshops in France or the products of the French munitions industry already in service with the French army. It was not uncommon for such weapons to be modified, sometimes extensively, to the detriment of having them conform to some preconceived idea of what a British munition should look like.

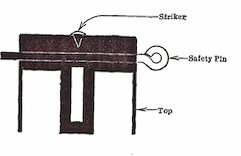

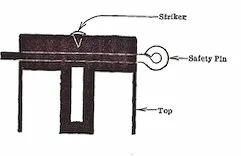

The staff of the Munitions Inventions Department were, by nature, conservative and risk-averse, and they examined the Pippin grenade; they were horrified by the absence of easily recognisable safety features. As the only mechanism preventing accidental depression of the firing cap was the four lugs that held the tin cap onto the grenade body, they recommended that the grenade needed to be made safer before it was fit to be issued by the Ministry. To this end, a large safety pin was inserted through the cap to prevent it from being accidentally pushed down and setting the grenade off, a fault rarely reported with the grenades produced by the Second Army Workshop and then only through misuse.

The safety pin was inserted through the cap of the Pippin rifle grenade.

To accommodate the safety pin, the cap had to be made more substantial, making it heavier. This was introduced into service as the Mark I Pippin Rifle grenade (No 22) and soon after its introduction reports began to come into the Experimental Section at GHQ of a fault, not seen in the Pippin rifle grenades still produced by the Army Workshops, namely prematures, with the grenade exploding at the muzzle of the rifle, sometimes causing death and injury to troops in the vicinity.[10] These were so frequent that rifle grenadiers took to tying a lanyard around the trigger of the rifle and taking refuge behind a trench traverse before jerking on the lanyard to fire the rifle, a mode of firing that did nothing for accuracy, as the pull on the lanyard invariably moved the rifle slightly out of position.[11] In the BEF, all accidents involving munitions were investigated by the experimental section and, as this was an army matter, the Ministry of Munitions, which manufactured the offending grenades, was unaware of any problems until Dr Christopher Addison, Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry, received a private letter from Lieutenant-Colonel David Davies MP, Commanding the 14th Royal Welsh Fusiliers, informing him of two fatalities in his battalion from a pippin grenade bursting prematurely at the muzzle of the rifle.[12]

Davies’ two young bombing officers, Second Lieutenants Williams and Pugh Jones, identified the heavy cap as the cause of the prematures suggesting that when the rifle was fired the force of the propellant drove the grenade forward but, for a fraction of a second, the heavy firing cap remained stationary (known as set back) allowing the primer cap of the cartridge case to engage with the striker pin causing the grenade to explode while still on the rifle. causing death and injury to all in the vicinity. They proposed to fit a ‘creep’ spring under the cap to prevent the grenade body from coming into contact with the firing pin at the moment of discharge, but not strong enough to prevent that from happening when the grenade hits the ground. This was rejected by Addison, who took the grenade away from the Munitions Invention Department and tasked the Trench Warfare Supply Department to find a solution and, in the meantime, recommended that the number 22 Mark I be withdrawn from service. The Trench Warfare Supply Department suggested that, rather than the creep spring to prevent a premature explosion, a thin strip of tin could be inserted between the firing pin and the detonator, strong enough to resist penetration by the firing pin during discharge but not when the grenade cap hit something solid. They also proposed reinstating Newton’s light tin cap, and when these modifications were accepted by the Ordnance Committee in October 1916, the grenade was reissued as the Mark II Pippin rifle grenade.

[1] TNA: WO95/1397/1: 3rd Division HQ. Commander Royal Engineers. War Diary, Entry for 26 November

[2] TNA: WO95/1397: 3rd Division HQ. Commander Royal Engineers. War Diary, Entry for 9 March 1915.

[3] A rifle battery was a device that allowed several rifles to be fired as a volley, usually at a pre-targeted spot of known enemy activity such as ration drops, or cross-roads, behind their trenches.

[4] Work of the Royal Engineers in the European War 1914-19: Machinery, Workshops and Electricity. The Naval & Military Press; Reprint Edition. (February 2009)

[5] French suppliers, sensing a profit from the supply of items that the army urgently required sold them with a heavy premium.

[6] The records of the Hazebrouck factory were one of the many casualties of the German Spring Offensives of 1918 and Henry Newton’s personal papers, which were extensive, destroyed in a house fire.

[7] Anthony Saunders, A Muse of Fire – British Trench Warfare Munitions, their Invention, Manufacture and Tactical Employment on the Western Front, 1914-18. (PhD Thesis. University of Exeter, 2008), p. 266

[8] A.L.C. Neame, Manufacture and Use of Hand Grenades. The Royal Engineers’ Journal March 1909, pp. 165-167.

[9] R. L. McClintock, An Extemporised Hand Grenade. The Royal Engineers’ Journal April 1913, pp. 193-200

[10] These caps are only found on the home-produced Mark 1 Pippen rifle grenade. Newton’s design, being an unofficial grenade and not produced under instructions from the War Office, did not have a number.

[11] I am grateful to Lieutenant-Colonel Norman Bonney for discussions on the cause of prematures in the Mark I Pippin.

[12] David Davies of Liaudinam (1880-1944), first Baron Davies. Became Liberal MP for Montgomeryshire aged 25. Raised and commanded 14th Royal Welsh Fusiliers. In 1916 appointed Parliamentary Secretary to Lloyd George. Like others of his family, he used his fortune for the benefit of Wales and its people. One of the founders of the League of Nations.

Chapter 2. Part 2.

Second Army Workshops.

Captain Henry Newton, 1/5 Battalion Notts & Derby Regt. (Sherwood Foresters) T.F.

Note: These drawings date from 1917and show the late version of the grenade with the tin safety strip inserted between the tip of the firing pin and the primer of the 0.303 cartridge case.