Chapter 2

The Cottage Industry.

Part II

The Army Workshops.

The First Army Workshop or Bomb Factory. Bethune

Introduction.

Between 1914 and 1918, the Royal Engineers created dozens, if not hundreds, of workshops. Most were small and are now forgotten, but they manufactured items necessary for units to address challenges specific to their own local experience of trench warfare. In addition to this plethora of small workshops, two exceptional organisations were created: the First and Second Army Workshops. From early 1915, these provided the BEF with many novel items of equipment required for trench warfare. They also became centres of invention and innovation. Many of the items developed there were repatriated home, initially by the War Office and later, on a greater scale, by the Ministry of Munitions. At home, these items were redesigned for factory production and issued to the army in large numbers, although their origin was forgotten and is now often attributed to the Ministry of Munitions.[1]

These workshops were extremely important in supporting the BEF's fighting ability throughout 1915 and into 1916. However, we have little information on their organisation or output. Created by an army on active service, these workshops fell outside the official War Office War Establishment. As a result, they were not required to maintain an official record of their activities, such as a War Diary. Furthermore, even the term 'army workshop' is a misnomer. In reality, these, especially the Second Army Workshop, were substantial munition factories that employed several hundred French civilians and contributed significantly to a local economy ravaged by war.

First Army Workshop. The Bethune Factory.

The Bethune factory has its origins in the bomb factory developed by these Sappers and Miners of the Indian Corps in November 1914. When First Corps relieved the Indian Corps in December, Lieutenant Bateman R.E. handed over First Corps' bomb factory in Bailleul to the 3rd Division, Second Corps. Subsequently, he moved with his Sappers to take over the running of the Bethune factory, including its civilian workforce. As a result of the reorganisation of the BEF into the First and Second Armies, the BEF Workshop became the First Army Workshop in early 1915.

The Bailleul workshop was critical in preparing Haig’s First Army for the BEF's offensive battles of 1915: Neuve-Chappelle, Aubers Ridge, Festubert, and Loos. Consequently, the workshop expanded, with its civilian workforce increasing by some 250, and many local companies acting as subcontractors, producing many of the non-munition items essential for trench warfare, such as duckboards, sandbags, and a wide assortment of boxes and containers, euphemistically referred to as trench furniture. The first real test of the bomb factory's ability to support the First Army in offensive action came with preparations for the Battle of Festubert in May. In the sodden landscape of the Lys valley, verging on marshland in places, the local farmers transported materials and harvested crops across their fields using hand-pushed trucks running upon a wooden tramway track made in sections and only lightly fixed to the ground so it could be taken up and moved around as required, a mode of transportation adopted by First Army to move supplies up to the front line with the tramway and trucks manufactured by experienced local firms from materials provided by the army, supplemented by the Bethune factory manufacturing large quantities of 60 cm wooded tramway track, along with the trucks.

We are fortunate to know something about the trench warfare material provided to the First Army, for on February 21st, 1915, the 2nd Infantry Division issued instructions to its new battalions on the method of obtaining supplies of trench stores.[2]

There were three issuing depots, the Divisional Ammunition Column, the Divisional R.E. Park and the Bethune Bomb Factory, each providing a different range of stores and infantry battalions obtained what they needed, not by applying directly to the Depots but through the Divisional Field Companies, presumably to allow the Quarter-Master’s Branch to collate requirements across the Division and ensure that sufficient supplies were available at each issuing depot. The R.E. Park was the source of general engineering supplies necessary to maintain the trenches, such as picks, shovels, barbed wire, sandbags, steel loopholes and grapples for pulling aside the enemy cheveaux de fries and wire out of the way. The Divisional Ammunition Column issued standard munitions approved by the Army Council, such as bombs and detonators for the 3.7-inch Woolwich trench howitzer, cartridges for Very Pistols, the No. 1 Service hand grenade, and the Hales hand and rifle grenades. They also issued approved emergency grenades, such as the double-cylinder, manufactured under War Office contracts.

The Bethune Factory produces the following,

Hand Grenades, Cast Iron.

Hand Grenades, Hairbrush.

Nobel’s fuze lighters.

Bombs for a 95 mm trench mortar.

Bombs for 93 mm trench mortar.

Trench Bailers.

Pumps local pattern.

Grenade bandoliers.

Sniper’s rifle rests.

Wooden loophole frames.

Steel hangers for steel loophole plates.

95 mm Trench Mortars.

Periscopes, box pattern.

Periscopes, single mirror pattern.

Ladders.

During the Festubert offensive, the factory increased munitions output. To breach German wire, dozens of 30-foot Bangalore torpedoes were produced in 10-foot sections to be assembled by infantry upon arrival. To address enemy bunkers and defensive structures, the factory engineered a new incendiary bomb. This device used petrol, ignited by a glass vial of sodium that shattered on impact. The sodium ignited on contact with traces of water in petrol. Although these bombs performed reliably in trials, there is no evidence of their use in the battle.

The Bethune Factory was also the origin of several critical innovations adopted by the Ministry of Munitions. Among these, their most notable was the Bethune Hand Pump, developed to pump liquid mud and water from trenches; this became standard army issue, produced in the thousands by the Ministry of Munitions throughout the war. In addition to such innovations, the workshop responded swiftly to emergency demands. For example, its first experience of a rush job involved supplying protective face masks for the First Army after the German gas attack in April. The factory produced 60,000 masks within a week - an impressive feat of improvisation and organisation.[3] The masks were based on the design of the chloroform mask used to anaesthetise surgical patients: a wire frame shaped over wood, with cross wires twisted by hand rather than soldered, and then covered by three layers of flannel. Large working parties of infantry handled the repetitive task of making the wire frames, and almost every French woman in the area was recruited to finish the masks by fitting the layers of flannel. When subjected to a gas attack, infantry were to dip their masks in sodium thiosulphate solution stored in the trenches, then tie the mask with tapes around the back of the head to cover the mouth and nose.

The introduction of the Mills bomb posed new challenges for the bomb factory. Most infantrymen could only throw the 1½ lb bomb twenty to twenty-five yards, which was not always far enough. To address this, the Bethune factory became the first to produce a cup attachment for a rifle. This was a conical cup, 5 inches tall, which screwed onto the rifle’s muzzle and was shaped to hold the grenade. A small recess at the top of the cup held the lever in position once the pin had been withdrawn.

To fire, a 4-inch steel rod was inserted into the rifle so it hung just below the grenade cup. This rod was designed not to fall down the barrel and, unlike rods in more familiar rifle grenades, was not attached to the grenade. When fired, it acted as a push rod, projecting the grenade about 60 yards with high accuracy. Large numbers of these cups and rods were manufactured before they were replaced by the more familiar launcher cup for the Mills bomb. Two other inventions of the bomb factory were widely adopted across the BEF over the winter of 1915/16: a muzzle-pivoting machine gun mounting and a Lewis gun sniperscope.[4]

The Battye Hand Grenade.

By February 1915, the Bethune factory was no longer producing jam tin grenades. They had been superseded by one of their own inventions, the Battye grenade, developed by Captain B.C. Battye R.E., of the 21st Bombay Sappers and Miners, was designed to be manufactured with the resources available in the Bethune.

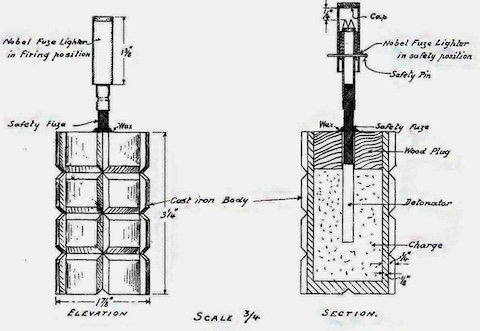

The Battye Hand Grenade. Graham M Ainslie, Hand Grenades. A Handbook on Rifle and Hand Grenades.

(London: Chapman & Hall Ltd. 1917).

Sometimes referred to as the Bethune Bomb, the Battye was a simple cast-iron cylinder measuring 3 by 2 inches, heavily scored on the outside to facilitate fragmentation. It contained 1½ oz of ammonal and was closed at the top with a wooden plug. A detonator, attached to a 5-second Bickford safety fuse that ended in a Nobel igniter, poked through the plug. The grenade was cheap and easy to make. As in British grenade factories, jobs like preparing moulds and filling bombs with explosives were often done by women and girls.

As with many other munitions developed in the bomb factories, the Battye bomb was repatriated home for factory production and redesigned by the Munitions Invention Department of the Ministry of Munitions. into the No. 13 and No. 14, light and heavy Pitcher hand grenades, much to its detriment. The significant difference between the Pitcher grenades and the original Battye was that the former used a friction fuse rather than the Nobel igniter, which, in theory, should have provided a better ignition system. In practice, the opposite was true. The friction fuse was very prone to dampness, resulting in a significant number of duds, but a greater fault was that, if not carefully handled, it was prone to premature explosions. These were so frequent that the bombers in training referred to themselves as the suicide club. These grenades are discussed later in the grenade chapter.

Grenades Available by March 1915.

An indication of the variety of grenades available to the First Army in March 1915 is provided by those recovered by the 8th Division's salvage teams from the battlefield of Neuve Chapelle.[1]

G.S. & HALES………………….282

BETHUNE……………………...548

DOUBLE CYLINDER……….…112

JAMPOTS………………………216

* HAIR BRUSH………………… 2

* RIFLE: GERMAN …………….14

* BOMBS, HAND, GERMAN ..…5

TOTAL. 1179.

* German: Hairbrush may have been originally British but were found in a German store.

NOTE: We cleared 7th Division area as well as our own.

VINETTE: Grenade Supply for the Battle of Loos.

The demand for Battye grenades by the First Army for the Battle of Festubert overwhelmed the manufacturing capacity of the Bethune factory, leading to an overhaul of the supply chain to increase efficiency and ensure that there would always be sufficient grenades to meet the First Army’s requirements. This was fortunate for the factory, which was called upon to meet an unexpected demand for Battye grenades during the preparations for the Battle of Loos. By September 1915, the Battye grenade was old technology, and GHQ planned to phase it out, replacing it with the new Mills bomb in time to equip First Army for its “Great Push” in September. Unfortunately, the Trench Warfare Department, responsible for organising the supply of the Mills bomb, had encountered production difficulties, and the grenade would not be available at the start of the battle. To supply the army, the department turned to the Bethune factory and ordered them to make as many Battye grenades as possible, but the number they could make in the time available, 80,000, was far short of the number required by the First Army.

To cover the shortfall, the Trench Warfare Department reverted to an even older technology, the Ball grenade. The BEF had phased out this grenade during the summer of 1915, but it was still manufactured as ammunition for the trench catapults used at Gallipoli, and the Trench Warfare Department increased production to meet the needs of the First Army. The original plan was to fit these Ball grenades with the Nobel igniter, but with all the other demands for its fuses, the Nobel factories were unable to meet this increased demand, leaving the Trench Warfare Department no option but to fit Brock igniters to the majority of the Ball grenades. While this fuse was cheap and quickly made, it was not entirely waterproof, and as the opening days of the Battle of Loos were wet, most British grenades became nonfunctional. So, when the British infantry successfully penetrated the German trench lines during the initial assault, they were soon driven out by German counterattacks employing more effective grenades.

Following this failure, the Bethune Factory undertook a major piece of research to develop a better waterproof fuse, and after a couple of months came up with a workable friction igniter, but this was never produced for, at the end of 1915, GHQ ordered all extemporised grenades to be withdrawn and replaced by the Mills bomb. As the production of the Battye grenades was phased out, the factory switched over to the manufacture of the Newton ‘Pippin’ rifle grenade, reaching an output of 1,000 a day, which was sustained until the Pippin was withdrawn from service in early 1917.

[1] TNA: WO95/1680: 8th Division. War Diary, A & QM Branch, 19 September 1914 – 31 December 1915

[2] TNA: WO95/1305. 2nd Division, GHQ Headquarters Branch and Services: Adjutant and Quarter-Master General. War Diary, 4th August-30 June 1915

[3] The Work of the Royal Engineers in the European War, 1914 - 1918. Miscellaneous. (Chatham, W. & J. Mackay & Co. Limited 1926). https://archive.org/details/workremiscellaneousww1 p. 255

[4] For the technically minded, the engineering drawings of these devices are given in Plates III and IV in Work of the R.E. in the Great War 1914-1919. Miscellaneous.

[5] TNA: WO95/1680: 8th Division. War Diary, A & QM Branch, 19 September 1914 – 31 December 1915