Chapter 2 Part 3

GHQ Experimental Section

The GHQ Experimental Section.

One of the most important organisations created by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) during the war was the Experimental Section at General Headquarters (GHQ). Towards the end of October 1914, as the first Battle of Ypres drew to its bloody conclusion, the opposing armies, with the onset of winter, began to dig the first trenches of the Western Front. At British GHQ, Lieutenant-General G.H. Fowke, the Engineer-in-Chief to the BEF, was one of the first senior officers to realise that this change in the nature of the battlefield would create a demand for weapons suitable for trench warfare. Fowke would have been aware of what the Sappers and Miners of the Indian Corps were doing with grenade production and decided to create a similar set-up at GHQ to provide grenades for troops in the trenches around Messines. He instructed the Officer Commanding the 2nd Bridging Train, a component of the GHQ Reserve, to furnish an officer capable of producing grenades.

The officer chosen, Lieutenant E.S.R. Adams, Special Reserve R.E., was an experienced mechanical engineer in civilian life who had already produced what were probably the first extemporised grenades in the BEF when the army was fighting on the Aisne in September. Adams, with eight sappers, took the residents in a barn attached to the château at Tilques near St Omer, and over the next two months, they produced several thousand hairbrush hand grenades. After the Sappers and Miners demonstrated their trench mortars to Sir John French and his senior officers at GHQ, Fowke commissioned the production of several Indian “pipe guns” from the workshop of a small paper factory outside St Omer and Adams added the production of mortar bomb to his repertoire, sub-contracted the casting of the bomb casings to local French foundries in St Omer and Calais. At this time, Adams and his sappers also carried out a small number of research projects to improve the fusing system of the jam pot grenades and to find the best way to add shrapnel, in the form of nails, to the hairbrush pattern grenade.

Vinette: 2/Lieutenant Breeze and the Rocket gun.

Their first serious research project started in January 1915 when the War Office asked GHQ for an opinion on the latest invention of Colonel Lewis, the inventor of the Lewis gun. This was a mortar, light in weight, that fired a heavy bomb over 1,000 yards on the principle of a rocket. Lieutenant Adams thought the machine was inherently dangerous, and he and his sappers spent a considerable time trying to improve its performance and safety by assisting 2/Lieutenant Breeze, Colonel Lewis’s assistant, in his experiments. 2/Lieutenant Breeze, like Colonel Lewis, was an American who had come to Britain in 1913 as secretary to the American Ambassador and soon became so fascinated by the country that he became more British than the British. When war was declared, with the assistance of his influential friends, he acquired a commission in the Royal Horse Guards and the War Office. Presumably not sure what to do with an American citizen in a British uniform, they posted him to assist his fellow American, Colonel Lewis.

Lieutenant Breeze was killed by a premature explosion of one of the bombs on 14 March 1915.[1]

In his evidence to the Court of Enquiry, Adams reported that Lieutenant Breeze always fired the rocket gun himself, using a lanyard, but invariably stood too close to the gun, rather distaining about taking cover when firing, even though Adams and his Sappers remonstrated with him on several occasions about the dangers of standing too close. He dismissed their concerns, saying he knew what he was doing and would not tolerate anyone interfering with his experiments.[2] On the day of the fatal accident, the gun had been placed in a freshly prepared fire trench, but without traverses behind which those operating the gun could take cover, and 2/Lieutenant Breeze had fired 8 rocket bombs successfully, but the last exploded at the muzzle of the gun, killing him without damaging the gun. After Lieutenant Breeze’s death the Experimental Section continued trying to improve Colonel Lewis’ rocket gun but abandoned the project when they failed to find solutions to its major drawbacks, the very visible trail left by the rocket that clearly marked the site of the battery, and the erratic behaviour of the rockets which, given the right wind conditions, could turn back on itself aiming at the battery that fired it.

Lieutenant Breeze was not a member of the Experimental Section; he was Colonel Lewis’ assistant, and his fatal accident was the only death (or serious injury) associated with the Section throughout a four-year period of handling explosive munitions of British, French and German origin. This exemplary record was due to the skill and care of the senior NCO Sergeant (later Q.M.S.) Griffin, who invariably did all the dangerous tasks himself, such as examining unexploded enemy ordnance of unknown design picked up on the battlefield.

Reorganisation.

In March 1915, the Experimental Section was reorganised. The original 8 sappers were joined by Corporal S. Griffin R.E. and 8 tradesmen from the 29th Advanced Park Company. These appointments enabled the Section to conduct more advanced research and evaluations of trench warfare munitions. Explosive ordnance work became a major focus of their work and be, and because of their proximity to GHQ, they were considered a hazard to staff and civilians and were relocated to a barge on the nearby canal. This was fitted out as a workshop and was a significant upgrade on their barn, as it had a 5-hp petrol-driven motor that powered two lathes, one from Paris and one from the 29th Advanced Park Company.

For the first few months, Lieutenant Adams’s section had no defined status at GHQ; it was a group of sappers assembled by the Chief Engineer to manufacture extemporised weapons for trench warfare, but this was to change with their move to the barge. Sir John French appointed Lieutenant Adams Experimental Officer to the Engineer-in-Chief, with his sappers referred to as the Experimental Section. This was a local appointment, not recognised by the War Office as part of GHQ’s establishment, but it enhanced Adams’s influence and authority within GHQ, and his Section began to assume significant responsibilities. They became responsible for evaluating and reporting on all new infantry weapons and ammunition offered to the BEF for trench warfare, and carried out any field testing at the bombing and mortar training schools. Here they could draw on the staff’s knowledge and experience, which often led to improvements in the design and performance of the munition undergoing evaluation. Adams’s reports informed GHQ’s decision-making processes on whether to accept an item and provided important feedback to the research and development staff of the Trench Warfare Department and other research groups within the Ministry of Munitions and the War Office. By the end of the war, it was said that no munition or equipment designed for trench warfare - except chemical munitions that were handled by the Special Brigade - escaped testing and modification by the Research Section.

When Sir Douglas Haig became Commander-in-Chief, he moved GHQ to Montreuil-sur-Mer in March 1916. The Experimental Section went with him and took up residence in the outbuildings of a private house by the South Gate near the main Montreuil-Abbeville Road. They had two lathes, a drilling machine, a blacksmith's shop, an acetylene welding plant, and various bench tools. Haig tried several times to have Lieutenant Adams and his staff officially added to the Chief Engineer’s Establishment; this was rejected by the War Office on the grounds that there was no precedent for the army having its own experimental section.

1916 was an important year in the development of trench warfare munitions. The army in France was growing as the New Army Divisions completed their training, and large stocks of trench warfare munitions and other items of equipment were being accumulated for the offensive planned for the summer. Although the cost of each item was small, the volume of production was of major financial concern to the Ministry, and if the Trench Warfare Supply Department was going to continue to meet its commitments a reappraisal of the cost of its output was urgently needed. Almost all trench warfare materiél had originally been developed by Royal Engineer workshops to meet specific demands from the infantry in the trenches, or by the Trench Warfare Department, and, over time, many had been modified on an ad hoc basis as trench warfare evolved in complexity. As a consequence, there was no standard design or approved specification for many of the items in regular use and the bean-counters in the Ministry of Munitions saw it as an area where substantial savings could be made through standardisation of design and the choice of materials. Consequently, throughout 1916 a collaboration between the Experimental Section at GHQ, the Trench Warfare Supply Department and the Munitions Design Department in the Ministry of Munitions reviewed every item deployed in trench warfare, munitions and equipment such as trench barriers, parapet shields, clinometers for the rifle grenade stands, screw pickets for wire, torpedoes for destroying wire, and much else, all redesigned to achieve simplification of design, economy of materials, and ease of manufacture. The economies were significant.

Perhaps, as a consequence of this reassessment of trench warfare materiél, the Ministry of Munitions felt it was losing intimate contact with the needs of the troops in France and to remedy the situation decided to appoint an officer with current knowledge of the requirements of the army, and with sufficient engineering experience to contribute to the design of any items trench warfare materiél requested by GHQ. The obvious choice was Lieutenant Adams, who transferred to the Munitions Design Department in March 1917. His duties as Experimental Officer were taken over by Lieutenant C.G.H. Bellamy, and with this change in command, Sir Douglas Haig made another bid to formalise the status of the Experimental Officer and his Section. This time, the War Office agreed, and in June 1917, Bellamy was appointed a Staff Officer on the establishment of the Engineer-in-Chief. Throughout 1917, the work of the Experimental Section increased substantially, leading to the appointment of a second officer, a trained mechanical engineer, Lieutenant J. McAllister R.E. and who had already served two and a half years in the infantry.

The Experimental Section now consisted of:-

1 Major

1 Lieutenant

1 Q.M.S.

2 Corporals

10 Sappers

1 Clerk

2 Draughtsmen

With one boxcar for transportation.

In 1918, the significant increase in its workload with explosive munitions and concerns about the danger to the local population instigated another move, this time to a rented field where the necessary buildings were erected. At the same time, Major Bellamy was moved from the Headquarters’ offices to the new site, making the Section practically independent, although still responsible to GHQ. Experimental work focused on the development of new weapons, such as contact mines for anti-tank defence and the No. 44 anti-tank grenade, a very destructive device that, in the absence of German tanks to attack, proved equally effective in destroying pill boxes and other hardened forms of defence. Research also continued into improving existing munitions, such as the cup discharger for grenades, periscopes, body armour, improved machine gun mountings for both aerial and ground use, and the perennial difficulty of communication between aircraft and the ground. In April 1919, even though it had carried out important work throughout the war, and its current research was important for the future, the Experimental Section was suddenly terminated, and its skilled and experienced staff either demobbed or returned to normal army duties.

Vinette: Responsibilities of the Research Section 1917-1918.[3]

Experimental Work.

Investigation of new types.

Improvements of existing types.

Reports on the suitability of new types.

Investigation of accidents and general advice regarding:

(1) Hand grenades

(2) Rifle grenades

(3) Rifle grenade dischargers

(4) Grenade guns

(5) Firework signals for all branches of the service, including the R.A.F.

(6) Light machine guns

(7) SAA – including penetration tests of all types

(8) Loophole plates

(9) Parapet shields

(10) Body armour

(11) Periscopes

(12) Hyposcopes

(13) Smoke Generators

(14) Illuminating devices

(15) Message-carrying projectiles

(16) Mines

(17) Light mortars and mountings

Vinette: Example of Experimental Work on Grenades.

Jam Pot Grenades.

Before the adoption of the Mills bomb, one of the greatest drawbacks of grenades, at least as far as the infantry was concerned, was the use of an external time fuse. Grenades were creatures of the night, employed in trench raids, harassing enemy working parties or defending your own trenches from enemy raiders. During the five seconds it took a lit fuse to reach the detonator, its passage through the night sky was marked by a cascade of bright sparks that lasted long enough for an alert enemy to move out of the way and take cover. The answer was a percussion fuse, and the Experimental Section, after considerable research, developed two workable patterns, one for a rifle grenade, and the other for the hand grenade, but neither were adopted for, by the time they were ready, the Trench Warfare Supply Department had committed all of its available manufacturing capacity to produce the Newton Pippin rifle grenade, and GHQ had stipulated that the only hand grenade to be issued was the Mills bomb.

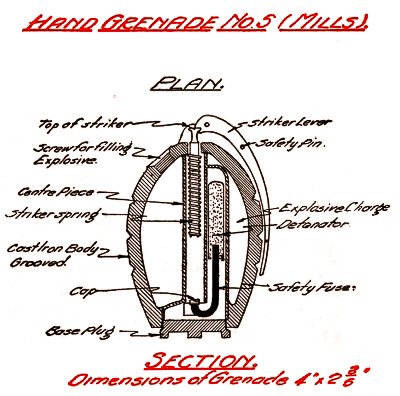

Mills Bomb.

Even the much-lauded Mills bomb was not without its faults. When first introduced and undergoing evaluation in the bombing schools, the Mills exhibited an unacceptable number of premature explosions, the grenade exploding as soon as it was thrown, or in the worst cases, in the hand of the hapless bomber. The Ministry of Munitions was aware of this fault but received insufficient information from the bombing schools to identify possible causes, as they were outside the loop when it came to investigating accidents occurring on active service. That was the role of the Experimental Section, which received reports from the Courts of Enquiry into munitions accidents. After identifying those attributed to human error, the Section was left with the unexplained and began carefully examining the factors that may have caused the accident, such as the munition's design. For the Mills bomb, two design faults were identified, which, when combined with poor manufacturing techniques, resulted in some grenades exploding prematurely.

J. S. Smith, Trench Warfare: A Manual for Officers and Men. E. P. Dulton & Co., New York, 1917. p112

In the Mills grenade, the 5-second delay between primer activation and grenade explosion is provided by a short length of safety fuse, one end attached to the primer cap and the other to the detonator embedded in the high explosive. A potential fault with this system is that the hot gases produced by the burning fuse may cut it short, reducing burn time and leading to a premature explosion of the grenade. To prevent this happening the holder for the striker cap at the top of the fuse had a number of holes drilled in it to allow the hot gases to escape, but in some of the grenades, due to poor machining during manufacture, the movement of the striker and spring on activation of the grenade, resulted in most becoming blocked, causing the very fault they were designed to prevent. The Experimental Section corrected this fault by suggesting alterations to the design of the striker.

The second fault was a failure of the safety mechanism. To activate a Mills bomb, the safety pin is withdrawn with the striker lever held down, and when the grenade is thrown, the handle flies off, releasing the firing pin to activate the time fuse. Once the safety pin had been withdrawn, the grenade remained safe as long as the thrower held the lever down, but in some batches of grenades, they exploded prematurely in the hand of the thrower before the lever was released. The bombing schools discovered empirically that these premature explosions could be prevented by grasping the lever tightly against the grenade body after withdrawing the safety pin, a safety manoeuvre all too likely to be forgotten in the heat of battle. The Experimental Section demonstrated that this fault originated in the design of the jaws on the lever, which, if poorly made, released the striker when the lever moved slightly with the withdrawal of the safety pin, an act prevented by pressing it tightly against the grenade body. The Experimental Section corrected this fault by recommending a modification to the jaw design so that the striker was not released until the lever flew off during the throw.

Rifle Grenades.

Before the introduction of the cup discharger for rifle grenades, they were fired by adaptations of the method patented by Marten Hales, which attached a firing rod to the base of the grenade, inserted it into the rifle barrel, and fired it with a special blank cartridge. This method of firing grenades damaged the rifling, making the rifle unsuitable for standard ammunition, so such rifles were kept exclusively for discharging rifle grenades. As the use of rifle grenades became more common in early 1916 a serious fault began to be reported in those rifles that were in constant use, the walls of the barrel became weakened and started to balloon out, a fault, if not detected early eventually led to the barrel bursting leaving the hapless grenadier with a live grenade attached to the top of his rifle. Resolving this problem was one of the Experimental Section's achievements.

The common rifle grenades in use were the No. 3 Hales with a 10-inch firing rod, and the Pippin and the No. 23 Mills grenade, both with a rod of approximately 6 inches and the bulges developed opposite the base of the firing rod, no matter which grenade was used. At first, it was thought that the bulging was due to excessive pressure building up as the propellant gases hit the base of the rod, but experiments with gas checks ruled that out, and further careful experimentation by the Experimental Section traced the cause to the wax plug used to seal the blank cartridges. In the original specification, drawn up by the Ministry of Munitions, this was specified as varnished tallow but several manufacturers, for cheapness and ease of use, substituted beeswax which, when the cartridge was fired, momentarily caused the rod to become stuck in the barrel of the rifle allowing excess pressure to build up hat weakened the barrel and the formation of a bulge. A fault was eventually corrected when the Research Section substituted a plug of waxed paper for pure wax to seal the top of the cartridge.

[1] 2/Lieutenant Breeze is buried in Longuenesse (St. Omer) Souvenir Cemetery Plot I. A. 56

[2] TNA: MUN 4/33 Proceedings of the Court of Enquiry held on 19 March 1915

[3] The Work of the Royal Engineers in the European War 1914-19. September 1924. Experimental Section p 455.