Technological Transfer from the Indian Corps to the BEF. (Chap.1 Pt. 4)

The First Demonstrations.

With much of the published history of the BEF focusing on the infantry and the battles they fought, there is a danger that other aspects of the war, insignificant in themselves but with a significant impact on the way the army fought, remain in obscurity. One such event is the technological transfer of the design, production, and tactical utility of light trench motors and grenades from the Indian Corps to the wider BEF in late 1914.

On November 21st the Sappers and Miners of the 4th Field Company1st King George’s Own Sappers and Miners demonstrated their new trench mortars to Sir James Wilcox, G.O.C. Indian Corps, his senior officers and representatives from the French 10th Army. [1] There is no surviving description of the mortars used in this demonstration but, given the early date, they must have been guns based upon Major Patterson’s design. News of this event reached GHQ, which requested its own demonstration. This was organised by Lieutenant-Colonel Twining and, on November 27th, accompanied by Lieutenant Bird and his mortar crew, they presented themselves at GHQ for a demonstration before Sir John French, his senior officers, and French representatives. The demonstration was a resounding success, and although we do not know which mortars were used, it is reasonable to assume that the Sappers and Miners wished to impress their audience and used their latest pattern, designed by Lieutenants Trevor and Fairly and completed and test-fired the previous day. This was their tripod gun, which had a barrel of carefully chosen steel pipe, 75 mm in diameter, supported on tripod legs that allowed the barrel to be slightly elevated, depressed, and traversed. The mortar tube rested on a detachable steel plate, or spade, which prevented the recoil from driving it into the ground and the gun, together with the legs which folded easily, weighed 50lbs and could be carried along a trench by one man. It fired a 4-pound bomb with great accuracy at ranges between 50 and 300 yards.

Sir Douglas Haig. First Adopter of Trench Mortars.

Among the observers was Sir Douglas Haig, Commander of I Corps. He was so impressed by the potential of the trench mortar that he cleared his diary and spent most of the following morning with the Sappers and Miners discussing their developments in hand grenades and trench mortars and receiving a first-hand account of Lieutenant Robson’s successful use of grenades in clearing enemy trenches. In modern parlance, Sir Douglas Haig had become an enthusiastic First Adopter of the new technology. He played an essential role in ensuring that the BEF adopted the light trench mortar.

This may come as a surprise to some, for as J.P. Harris points out in his essay on Haig and technology,

One of the many criticisms made of Haig’s command of the British Expeditionary Force during operations on the Western Front from December 1915 to November 1918 is that he failed to understand and exploit the potential of the latest technology. [2]

As John Bourne has remarked that, despite a great deal of evidence to the contrary, the view persists that Victorian Cavalry officers, such as Sir Douglas Haig and Sir John French, were intrinsically incapable of understanding technology but why this view is justified is rarely explained for, in the military spheres of the cavalry and transport, successful horse management was as complex, and as technologically driven, as many other aspects of the Edwardian army. [3] I share with Harris and others, the slightly unfashionable view that this criticism is uninformed for Sir Douglas Haig, throughout the war, championed the introduction of new technology and new methods of working as a means of hastening victory and sparing the lives of his soldiers. [4] Examples abound. His support for trench mortars is considered here; the use of gas at Loos; his advocacy of the 4-inch and 3-inch Stokes pattern mortars; and the employment of the Tank. As far as his support for new methods of working, we need look no further than his overhaul of the BEF supply system, bringing in civilian experts such as Eric Geddes and granting them authority. Haig even gets criticised for his enthusiasm for advances in technology, as this led him to rush their introduction onto the battlefield before they were ready, resulting in dramatic failures on their first deployment. The oft-quoted examples are the use of gas at Loos and Tanks at Flers-Courcelette on the Somme, an argument that relies too much on hindsight and a desire to re-order events of a hundred years ago. These two examples are no different from the introduction of other novel trench warfare munitions, such as grenades and trench mortars, that were introduced when still in the developmental or even experimental stage, to be rapidly improved once feedback on their use was available.

In December 1914, Haig’s I Corps consisted of the 1st Division, supported by the 23rd and 26th Field Companies RE and the 2nd Division, supported by the 5th and 11th Field Companies RE and on returning from his visit to the Indian Corps Haig instructed his Field Companies to send an officer to his HQ the following morning to be briefed on his visit before joining the Sappers and Miners for instruction in the production of hand grenades and trench mortars.

2nd Division Workshop.

The visit of Royal Engineer Officers from the 2nd Division to the Indian Corps took place on the December 1st, and the next day the War Diary of the 5th Field Company records that they had acquired a local workshop and started manufacturing grenades. [5] This bomb factory was to remain small and struggle to make trench mortar and ammunition with the resources at its disposal.

1st Division Workshop.

Lieut-Colonel A. L. Shreiber, CRE 1st Division, decided that with the 2nd Division workshop in the Hazebrouck area, there were insufficient resources to develop another bomb factory and instructed Lieutenant Bateman from the 23rd Field Company RE, a French speaker, to survey the facilities available in Bailleul and its neighbourhood.

Bateman found a somewhat rundown engineering workshop in the Rue D’Occident, complete with a selection of lathes, drilling machines, standard bench tools, and a small furnace suitable for melting iron. Adjoining was an equally rundown, but still functional, carpenter’s shop, also available to lease. His survey of the town’s resources identified local suppliers of angle iron for the mortar supports and a supply of thin zinc sheets, ideal for making bomb casings, but little solder with which to weld the sheets into shape. He also acquired 16 lengths of cast iron water piping, about a meter long and of 94 mm bore that he judged strong enough for mortar tubes. [6] On December 4th, with a complement of 25 Sappers of various trades, Bateman completed their move into the workshops and commenced the manufacture of trench mortars and grenades. [7] The next morning he was allocated a motor lorry and went to Armentières to purchase materials for his workshop including 11 lengths of steel water pipe 93 mm in diameter, four of which were given to the 2nd Division for mortars to be constructed by the 11th Field Company in Hazebrouck. With both Divisions manufacturing trench mortars on different sites, coordination and agreement on design and dissemination of best practice was achieved through regular meetings of the Divisional Commander Royal Engineers, instigated by Brigadier-General S.R. Rice, RE, Chief Engineer to I Corps. [8]

Lieutenant Bateman’s first two steel tube mortars were tested on the 8th of December with five dummy bombs and one live, which exploded well. The maximum range achieved was 184 yards, improved to 226 the following day. In his report on the trial, Major Pritchard (O.C. 26th Field Company RE) drew attention to the poor facilities for bomb-making in Bailleul. It had taken three days to complete 19 bombs. [9] I Corps GHQ immediately rebuffed his pessimistic report,

On December 10th, Major Pritchard reported that they had completed four mortars and that the parts for 60 shells were complete; another 40 were almost so, but so far only 24 had been filled with explosives, and it had taken a week to produce this number.

The novelty of the bomb factory soon presented the 1st Division with an organisational issue. The Indian Corps recognised the importance of continuity and the need to muster skills in one place. They created their bomb factory by removing the Sappers and Miners necessary to its functioning from routine trench duties. The 1st Division had yet to reach the same conclusion for Major Pritchard, in preparation for his Field Company returning to the trenches, informed HQ that he proposed to cease all manufacturing activity as soon as they had completed the current batch of 100 mortar bombs. This seems to have goaded I Corps into action, and Lieutenant Bateman and an unknown number of Sappers were ordered to remain behind to continue operations in the workshop. They were also transferred out of their Field Company, coming under the command of the Commander, Royal Engineers 1st Division, who was to assume responsibility for the day-to-day running of the Bailleul workshop. [10]

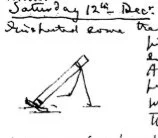

On December 12th, Haig made his first inspection of the Bailleul workshop, remarking on how impressed he was with the work of Bateman and his Sappers, and adding a marginal sketch of their mortar in his diary.

Sketch of I Corps’ trench mortar. Haig’s diary, 12 December 1914.

Following the visit Haig went on to a meeting with Sir John French and General Smith-Dorrien to discuss II Corps involvement in the upcoming French offensive against the Messines Ridge and when discussing tactics it transpired that that II Corps, or at least the 3rd Division who were to conduct the attack, did not possess any trench mortars and Haig, probably pleased to get one over Smith-Dorrien in the presence of Sir John French, offered some of his, which were accepted with Haig recording in his diary, rather smugly I think,

I offered my trench guns, and four are to be sent to the II Corps and 4 to the III Corps. Neither Corps had apparently started to make any. They seemed to me rather slovenly in their methods of carrying on war. [11]

That afternoon, the 26th Field Company was instructed to hand over four of their precious mortars with a hundred rounds of ammunition to II Corps.

Developments continued in the I Corps workshop as Haig moved to incorporate these new weapons in the Order of Battle. He adopted the Indian Corps practice of specifying a ration of 50 rounds per mortar, supported by a reserve of 50 rounds held in the Divisional bomb store. This commitment to 100 rounds per gun required extending the workshop, with Lieutenant Bateman requesting supplementary supplies to increase his weekly output to 350 mortar bombs and 700 grenades. At first, Haig did not follow the Indian Corps’ practice of training selected infantry as mortarmen; instead, he followed War Office orthodoxy and assigned his trench mortars to the field artillery. This was not a success for the gunners treated them as miniature howitzers, only to be fired in predetermined shoots at identifiable targets, and with his gunners reluctant to shoot at transient targets of opportunity identified by the infantry Haig put an end to this unsatisfactory situation by instructing the 26th Field Company RE to establish a school on the Indian model for the training of selected infantry officers, NCOs and men in the use of hand grenades, rifle grenades and trench mortars.

Transfer of Workshops.

On December 22nd, the Germans launched a powerful attack on the depleted and exhausted Indian Corps around Festubert, capturing a significant portion of the front line. To stabilise the situation and regain lost ground, I Corps was ordered to relieve the Indian infantry with urgency and retake the lost trenches. This was going to require an ample supply of grenades and to ensure that there was no breakdown in supply as the Indian Corps withdrew into reserve Bateman handed the Bailleul workshop, complete with its civilian labour force, over to II Corps, and transferred, with his men, to Bethune to take over the management of the Indian Corps factory along with its civilian workforce, a process completed on Christmas Eve. The Sappers and Miners maintained their grenade-making workshop at Gorre until I Corps could release sufficient sappers from the battle to replace them. [12]

On Boxing Day, the Lahore Division submitted their final report to Indian Corps HQ summarising their achievements over the previous month,

Up to the date of handing over, we had the following,

1. Nine trench mortars, of which eight were RE mortars and one brass mortar. The Germans captured six, and we handed three to the First Division.

2. We made and used about 4,500 four-pound gun bombs.

3. 9,000 one-pound jam pot bombs. 2,000 one-pound cast iron bombs. 6,000 two-pound hairbrush pattern bombs. That is three hundred jam pot bombs a day for a month, made by S and M Coys from about the fifteenth Nov to the fifteenth Dec. Three hundred cast iron bombs a day made by the factory from the fifteenth to the twenty-second December. Two hundred hairbrush bombs a day made partially by S and M Coys and partly by a factory from the twenty-first of November to the twenty-second of December.

4. Bomb factory established in Rue de Lille, Bethune, now being worked by 1st Div. [13]

The reserve of trench warfare munitions available to I Corps, a mixture of items left by the Lahore Division, and those brought from Bailleul, are given in Lieutenant Bateman’s inventory at the time he took over the factory,[14]

Mortars. One 95 mm Ind. Div. left by Lahore Div

One 96 mm believed to be arriving from GHQ.

Three 93 mm made in Bailleul by 26th Fld. Coy.

Mortar bombs for 95 mm bore.

800 stored Bethune.

150 Lahore Div.

100 unfilled made at Bethune.

Mortar bombs for 93 mm.

200 made at Bailleul by 26th Fld. Coy.

Hand Grenades. Cast Iron 19oz.

400 made at Bethune 23rd Coy.

200 made at Bethune 26th Coy.

300 made at Bethune.

Hairbrush pattern,

200 made by 26th Coy.

400 made by 23rd Coy.

300 made at Bethune.

In addition, there were 6,000 primers and detonators in stock which they proposed to use up at a rate of 1,500 a day for four days while they gained some estimate of the likely demand now that I Corps had returned to the line. Currently, their best estimate was for more than a thousand mortar bombs a day.

Refrences.

[1] TNA WO95/3938 War Diary. 4th Coy. King George’s Own Sappers and Miners. 21 November 1914.

[2] J. P. Harris, ‘Haig and the Tank’, in Brian Bond & Nigel Cave (eds), Haig. A Reappraisal 70 Years On (Barnsley: Leo Cooper, 1999). pp.145-163.

[3] J. M. Bourne, ‘Haig and the Historians’, in Brian Bond & Nigel Cave (eds), Haig. A Reappraisal 70 Years On (Barnsley: Leo Cooper, 1999), pp.1-11

[4] John Sneddon, ‘Sir Douglas Haig and the Introduction of the Trench Mortar 1914-1915’, RECORDS. The Douglas Haig Fellowship, 19. (2017), pp.11-27

[5] TNA: WO95/1330. 2nd Division 5th Field Company RE. War Diary, 2 December 1914

[6] TNA: WO95/1244: Report on facilities for making trench mortars & ammunition at Bailleul. 1st Division Commander Royal Engineers. War Diary, December 1914, Appendices

[7] To allocate this number of sappers away from the critical work required on the trench line is a level of commitment I Corps was willing to make to this new technology

[8] TNA: WO95/1244: 1st Division Commander Royal Engineers. War Diary, Appendix December 1914

[9] TNA: WO95/1244: 1st Division Commander Royal Engineers. War Diary, December 1914

[10] Once Bateman and his Sappers were detached from their Field Company, they were no longer on ration strength, and so no information on their activities is recorded in the unit War Diary. The bomb factories were considered temporary organisations created by a local commander and not required to keep a record equivalent to a War Diary. As a result, the scant information that has survived regarding their activities is usually found in the War Diary of the Divisional Commander, Royal Engineers.

[11] Sheffield, Gary & Bourne, John (eds), Douglas Haig. War Diaries and Letters 1914-1918. (London: Weidenfield & Nicolson 2005) Diary Entry. Saturday 12 December

[12] TNA: WO95/1244: 1st Division HQ. Commander Royal Engineers. War Diary, Messages and Signals. 22 December 1914

[13] TNA: WO95/3912: 3rd Indian (Lahore) Div. HQ. War Diary, December 1914. Appendix I

[14] TNA: WO95/1244: 1st Division HQ. CRE War Diary. Messages and Signals. 26 December 1914