Chapter 3. Part 6. Trench Mortars. Cape Helles.

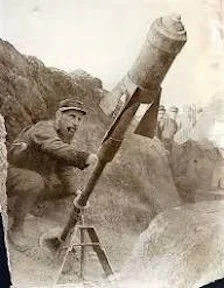

3.7-inch Light Trench Howitzer.

3.7-inch Light Trench Howitzer

The British that landed on the beaches of the tip of the Gallipoli peninsula had no mortars to assist them in overcoming the Ottoman defences, for at the time of the landings, April 25th, 1915, the War Office was unable to respond to Sir Ian Hamilton's frequent demands for trench mortars. The first batch of the Woolwich-manufactured 3.7-inch light trench howitzer was delivered to the BEF in January 1915, but these were defective, and it was not until early February that the production of the original order for 120 guns, all destined for the BEF, was resumed. Then, to his surprise, the War Office notified Sir Ian Hamilton on March 11th that they intended to provide him with twenty of the 3.7-inch light motors currently in production. However, when the War Office received confirmation that the Dardanelles Army would be equipped with Japanese mortars, they reduced their offer to ten 3.7-inch mortars, with a ration of 1,000 bombs each. When it became clear that the attempt to secure the Gallipoli peninsula was not going as well as expected, the War Office relented and restored the original offer of twnty mortars.

All twenty of the 3.7-inch mortars were deployed at Cape Helles. None were issued to the ANZAC Corps, and even then, 20 light mortars fell far short of the requirements for the length of front and intensity of the fighting being experienced by the British and Indian troops at Helles, a situation made worse by the totally inadequate ammunition supply. Deliveries from Britain were irregular and often interrupted by enemy submarine activity in the Mediterranean or by bad weather preventing landings on the exposed beaches of the peninsula. The bomb factory at Lancaster Landing lacked the machinery and other resources to manufacture mortar bombs, and although Garland and the Cairo Citadel tried to assist, the bombs they produced were so poorly made that most were useless. In many cases, the gas checks were badly fitted, and the bomb became stuck in the barrel when loading. The small ring attached to the top of the bomb for extracting stuck bombs was so weak that it could be easily pulled off, leaving the crew with the delicate, time-consuming task of removing the bomb without accidentally activating it.[1]

In late 1915, the 3.7-inch mortars on the Western Front were beginning to be replaced by the Stoke 3-inch light mortar, and the War Office took the opportunity of disposing of some redundant stock by sending a small number of the 3.7-inch M.K.III mortars to Gallipoli. They arrived in November, and VIII Corps divided its allocation as follows: three to the 42nd Division, bringing their total of all types of trench mortars to six; five to the 52nd Division, bringing their total to nine; and three to the Royal Naval Division, bringing their total to six. The ammunition ration for these guns, the delivery of which became even more erratic with the onset of winter weather, was set at 100 rounds per gun, of which 50 must always be kept in reserve to deal with any serious enemy offensive, leaving 50 rounds per gun per week.[2]

The French Mortars.

The French landed at Gallipoli better equipped than the British in almost every respect, including twenty-four 58 mm medium Dumézil trench mortars, of which 12 were type I, the other 12 the improved type II, along with 2,400 rounds of ammunition. The Dumézil were spigot mortars similar to the Japanese guns and fired either an 18kg or 35kg bombs. These were fitted with a percussion fuse, and the base was threaded to take the “tail”, a steel tube 58m in diameter. Four fins welded onto the base of the bombs to provide stability in flight and assist in attaining a maximum range of about 1,500 metres.[3] These mortars had great destructive powers but were prone to firing short, a serious handicap for when they came into action the trenches in the neighbourhood, particularly those to the front, had to be cleared of infantry.

The French Medium Mortar Dumézil Type1 and 2.

When the French withdrew from Gallipoli in December, they passed their mortars and remaining ammunition to VIII Corps. These were allocated to the Royal Naval Division and the French started training the first contingent on December 17 consisting of Lieutenant Fullerton of the Hood Battalion, with 5 Petty Officers and 5 men from the 1st Brigade, and a Petty Officer and 13 men from each of the other battalions in the Brigade, with the second cohort starting on the 20th.[4] On December 19 the Division informed VIII Corps that they would be taking over 10 Dumézil mortars from the French and proposed to form a Divisional Mortar Group under the command of Lieutenant Campbell.[5]

Were there 3-inch Stokes mortars on Gallipoli?

In late September 1915, a meeting between Dr Christopher Addison of the Ministry of Munitions, Arthur Balfour, the First Lord of the Admiralty and Sir Alexander Roger, Deputy Director-General of the Trench Warfare Supply Department, discussed the provision of mortars for the Dardanelles. Ever keen to promote his department, Roger informed the meeting that, notwithstanding the unmet demands from the BEF, his department could provide the necessary 2-inch medium and Stokes 3-inch light mortar whenever GHQ Mediterranean Expeditionary Force submitted an order.[6] This duly arrived in October, 200 Stokes and fifty 2-inch mortars, but without specifying their ammunition requirements. While they waited for the delivery, the Trench Warfare Department suggested that it might be useful for them to send out samples of the Stokes mortars with a small amount of ammunition so the troops could gain experience with them, but GHQ Mediterranean rejected the offer. They did not want the Turks to become prematurely aware of the new mortars, which they planned to use to spearhead a new offensive and were prepared to wait until a large supply of ammunition was available and, as an indication of their future requirements, placed an order for 200,000 rounds for the Stokes and 25,000 rounds for the 2-inch mortar.

The time available to meet the Dardanelles’ demand was constrained by the sailing date of the supply ship from Avonmouth, November 6th. The War Office was already sending selected officers and NCOs to the Trench Warfare Department training school on Clapham Common to train as instructors. The Trench Warfare Supply Department was also doing some forward planning, placing anticipatory orders in August with several suppliers for over 100,000 fuse heads, the most complex part of the mortar bomb, for delivery by the end of September. Then, after a delay, orders were placed for the manufacture of 800,000 empty bomb casings, again anticipating that the completed bombs would be ready for dispatch by the end of October.[7]

As the Trench Warfare Supply Department struggled to assemble the resources to meet the Dardanelles' order for 200 Stokes mortars and 100,000 rounds of ammunition, France immediately demanded 20 Stokes mortars and 5,000 bombs. Supplying the 20 mortars posed no problem, but the department faced difficulties manufacturing ammunition. Diverting 5,000 bombs to France would prevent them from meeting the Dardanelles deadline. Suspecting France intended to spoil the Dardanelles delivery and aware of the political gains the War Office could make if they failed to meet the BEF's request, the Trench Warfare Supply Department escalated the issue to the Minister of Munitions. In his memo to Lloyd George, Dr Addison explained the situation, noting that although the Ministry did not control bomb allocations after delivery to the War Office, sudden French demands disrupted Dardanelles supply planning. He suggested the War Council rule on priorities between the two theatres of operation.[8] However, before resolving the matter politically, manufacturing realities determined the fate of the Dardanelles' Stokes mortars.

When the first batches of bombs were assembled and tested in the middle of October, a potential fault was identified in some of the bombs; the striker of the trigger mechanism was failing to engage with the detonator cap, leading to a misfire. This fault was quickly remedied; unfortunately, the time required to implement the changes in the manufacturing process meant it was too late to fit the modified triggers to the bombs destined for the Dardanelles. They, along with the 200 guns, quite literally missed the boat, and no Stokes mortar ever reached Gallipoli.[9]

The newly trained instructors, along with the 200 guns, were allocated to the mortar training schools that were springing up all over Britain to train the New Army Divisions.

[1] TNA: WO95/4274: General Staff. VIII Corps. War Diary, Bomb Conference. 22/11/15. Appendix XXXI

[2] TNA: WO95/4274: General Staff. VIII Corps. War Diary, December 1915. Appendix. XX

[3] Manual for Trench Artillery. Part V. The 58 mm No.2 Trench Mortar. U.S. Army March 1918. Translated from the French. <http://cgsc.cdmhost.com/cdm/ref/collection/p4013coll9/id/253> (Last accessed July 2018)

[4] TNA: ADM 137/3065: Headquarters 1st Brigade. Royal Naval Division. War Diary, December 1915

[5] He was the son of the famous actress Mrs. Patrick Campbell, (Beatrice Stella Cornwallis-West). Mrs Patrick Cambell, My Life and Some Letters (London: Hutchinson & Co., nd)

[6] TNA: MUN 5/382/1600/6: History of the Trench Warfare Supply. Section IVa

[7] TNA: MUN 5/384.1611/1: p. 20

[8] Ms Addison c73 folio 70-75: Addison to Lloyd George

[9] History of the Ministry of Munitions. Vol. XI. The Supply of Munitions. Part I. Trench Warfare Supplies. p. 47