Military: British

This Blog hosts posts ot pages relating to the military activity of the British Army in the Great War 1914-18. This will include the Home Front; the Western Front; Gallipoli anf other Theatres of Operations.

The Indian Corps and the Introduction of Trench Mortars. November 1914.

The Indian Corps and the Introduction of Trench Mortars. November 1914.

The Royal Engineers of the Indian Corps kept the old title of Sappers and Miners, tracing their history back to the first British East India Company armies. From 1740, they formed three Corps of Sappers and Miners—one each for the Bengal, Madras, and Bombay Presidencies of the East India Company. Each Corps contained several companies of native craftsmen, led by British-trained Royal Engineers who sought these posts for action and the prospect of plunder. From the start, the Sappers and Miners earned a reputation for skill and bravery in the field.

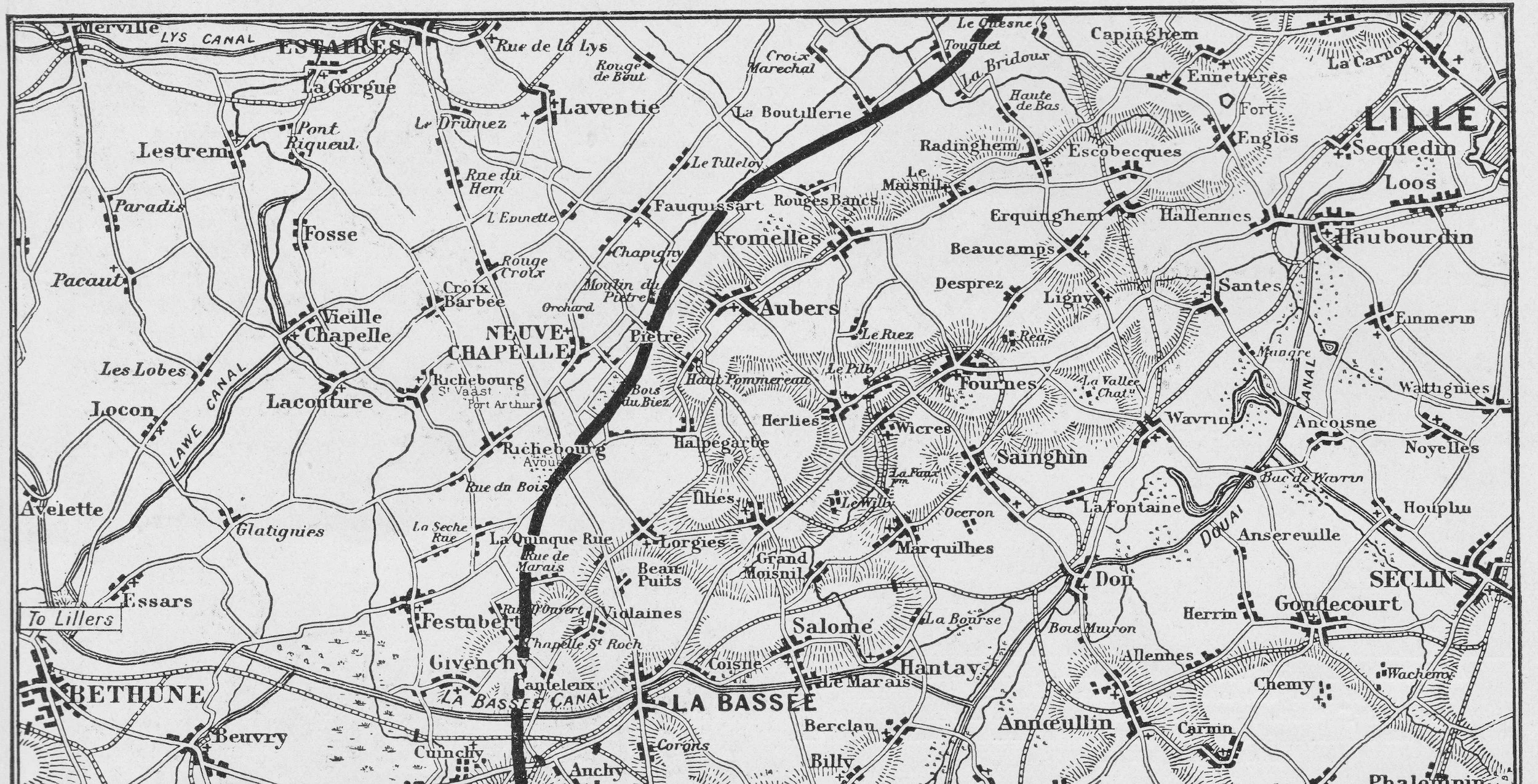

The Indian Expeditionary Force consisted of the Lahore Division, supported by the 20th and 21st Companies Bombay Sappers and Miners, and the Meerut Division, supported by No 3 and 4 Companies 1st King George’s Own Sappers and Miners. The Indian cavalry units used their own Field Companies. The Indian Corps landed at Marseilles on 26 September 1914, and by late October, after relieving the exhausted British II and III Corps the held the line between Éstaires and Festubert, close to the La Bassée canal, where they linked up with the trenches of the French 10th Army.

The Battlefield of the Indian Corps. The Great War. Part 68. 4 December 1915. (London: Amalgamated Press Ltd) p.104.

The Indian Corps were the first completed formation in the BEF to experience static trench warfare, and it is from this experience that they identified the tactical imperatives that gave rise to the demand for trench mortars.

This early battle zone was not the devastated landscape of later years, but still identifiable as farmland with hedges, woods, and many cottages and farm buildings, although damaged, were still standing, providing ample cover for German snipers, machine guns, and concealed entrances to the numerous saps that snaked out towards the Indian firing line. Field defences on both sides of No Man's Land were practically non-existent, consisting of a few strands of barbed wire strung on wooden frames, termed chevaux de frise, which, as they were not securely fixed to the ground, could be easily pulled aside to create a passage. In many places, the trenches were close —no more than 50 to 100 yards apart —providing a rich environment of potential targets, including working parties, saps, machine-gun positions, snipers, and the general infrastructure behind the firing trench, such as dugouts and store dumps. All of these were within the range of the early trench mortars with a maximum range of about 400 yards. It is important to appreciate that with these early trench mortars, range was less of an issue than the ability to deliver accurately a payload heavy enough to do some damage.

The Introduction of Trench Mortars. For the BEF, mobile warfare on the Western Front practically ceased around the 12th of September when the Germans, retreating after the First Battle of the Marne, halted the French and British advance from hastily dug trenches on the heights above the river Aisne. This was the British army’s first experience of trench warfare since the Crimean war, some 60 years earlier, but the professional soldiers of the BEF quickly appreciated that this represented a change in the nature of the battlefield and once the lessons from this short period of trench warfare had been digested Sir John French wrote to the War Office making his first request for trench mortars.

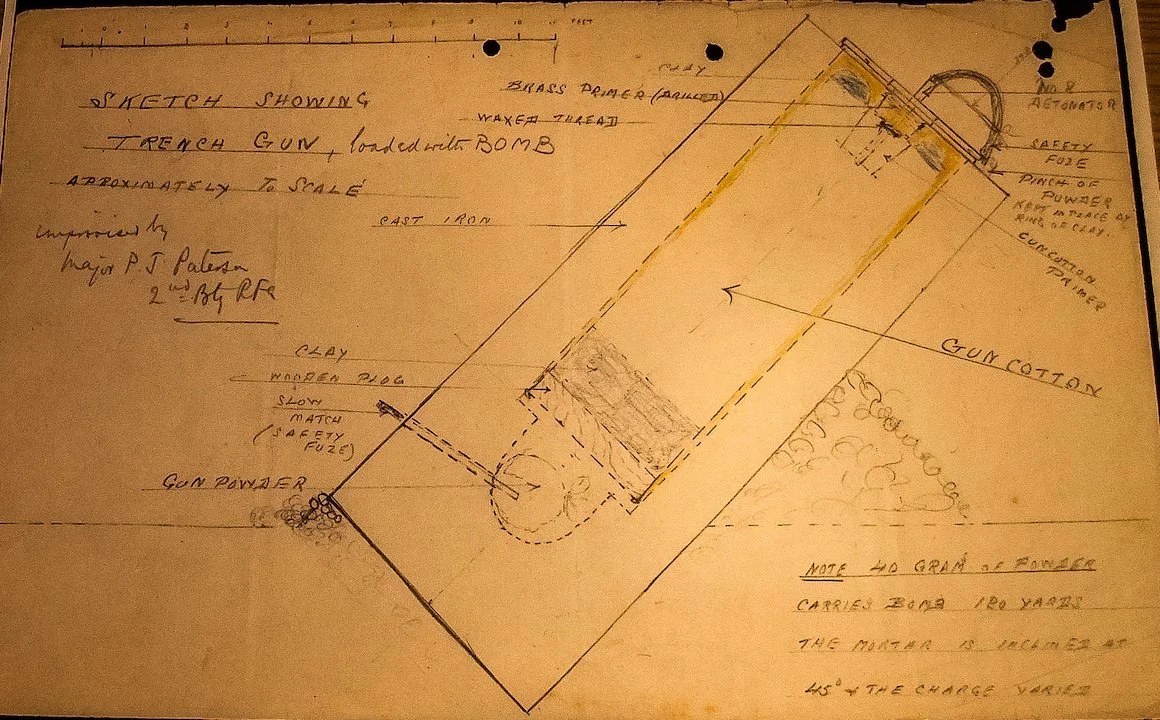

The Was Office and Woolwich Arsenal were slow to respond to this request, and the first trench mortars to be developed and used on the Western Front were developed by the Sappers and Miners of the Meerut Division. The catalyst for this event was Major P.J. Paterson, 2nd Battery Royal Field Artillery, attached to the Meerut Division, who, sometime during the first week in November, approached No 4 Company, King George's Own Sappers and Miners to enlist their help in constructing a mortar and bomb that he and his battery fitter had devised.

Major Paterson’s Bomb Gun. The first trench mortar to be fired at the enemy by the BEF. TNA: WO95/3937: War Diaries. Meerut Division. 13th Bde. Royal Field Artillery.

The mortar was constructed from a short length of cast-iron pipe, closed at one end, and fired with gunpowder contained in small bags made from sacking pushed down the barrel with a ramrod and fired with a short length of safety fuse pushed through a touch hole drilled close to the base of the barrel. The shells were 18-pounder brass cartridge cases with about 3 inches cut off the open end, and the brass plug on the base that held the fuze was drilled to accommodate a No. 8 detonator. When filled with high explosives and closed with a wooden lid, the shells weighed approximately 3 lb 12 oz. A short length of instantaneous fuse was attached to one end of 3 inches of slow fuse; the other end clamped onto the detonator, and the fuse was bent around the outside of the shell casing so that the instantaneous fuse was lit by the flash of the propellant just as the bomb left the barrel. The bombs did not slide down the tube, as was the case with later mortars, but rested on the mouth supported by the rim of the cartridge case. This type of ammunition was christened "Paterson's Pills for Portly Prussians." There was no supporting frame, so the mortar tube was propped up at a suitable angle with sandbags, and the range was adjusted by varying the angle or the number of small bags of gunpowder.

The first two mortars manufactured appeared to be experimental prototypes: one made from a length of iron pipe and the other from wooden staves bound with iron hoops, similar to the mortars used by the Japanese during the Russo-Japanese War. In the unit War Diaries, there are entries between November 12th and 17th concerning the development of the mortar. On the 18th, the two mortars, along with 20 rounds of ammunition, were placed in a front-line trench occupied by the Leicestershire Regiment. The next morning, Lieutenant Trevor, accompanied by an NCO and six Sappers from the 4th Field Company, became the first troops in the BEF to fire a trench mortar in anger at the enemy, landing three of the bombs on target, a particularly annoying German sap-head, much to the delight of the infantry. This first trial immediately suggested areas for improvement. The lack of a carriage to support the mortar tube impaired accuracy. The black powder should be sifted and weighed more accurately to improve consistency in range, and the sacking should be omitted, as it was blown burning from the gun, leaving a trail of smoke that disclosed the position of the mortar to enemy retaliatory fire. The mortars were successfully deployed again on the 20th and 21st, and the wooden mortar blew up when taken out by the inexperienced Company Sergeant Major Gibbon on the 23rd. Experience and experimentation steadily improved the mortar design, including a significant advance on the 2nd December, when bombs fitted with percussion fuses were tested; however, as they are not mentioned again, we must assume this line of enquiry was abandoned because the fuses were too challenging to produce in the quantities required.

Lieutenants Trevor and Fairley of the 4th Field Company introduced what were probably the most significant innovations in trench mortar design when they unveiled their new pattern on the 26th of November, a radical departure from Major Paterson’s prototype of only a fortnight before. This was their tripod gun, which had a barrel of carefully chosen steel pipe, 75 mm in diameter, supported on tripod legs that allowed the barrel to be elevated, depressed, and traversed. The mortar tube rested on a detachable steel plate, or spade, which prevented the recoil from driving it into the ground and the gun, together with the legs which folded easily, weighed 50lbs and could be carried along a trench by one man. It fired a 4-pound bomb with great accuracy at ranges between 50 and 300 yards.

This was the model adopted for production, and six were in action with the Corps by the end of November, with ten more due for completion during the first week in December, giving a total of sixteen —two per battalion for each of the Infantry Brigades in line. The ammunition was surprisingly sophisticated, considering the Sappers and Miners were not equipped with machine tools such as lathes and other metalworking machinery. Still, it was always possible that such machine working was contracted out to local French engineering workshops. According to the War Diary, the model for their mortar bomb was a German dud. No details or diagram of this German bomb appear to exist, which is a pity, because if it were the model for the Sappers and Miners’ bomb, it suggests it was fired from an extemporised mortar rather than a regular minenwerfer that fired a sophisticated shell similar to that used by the artillery.

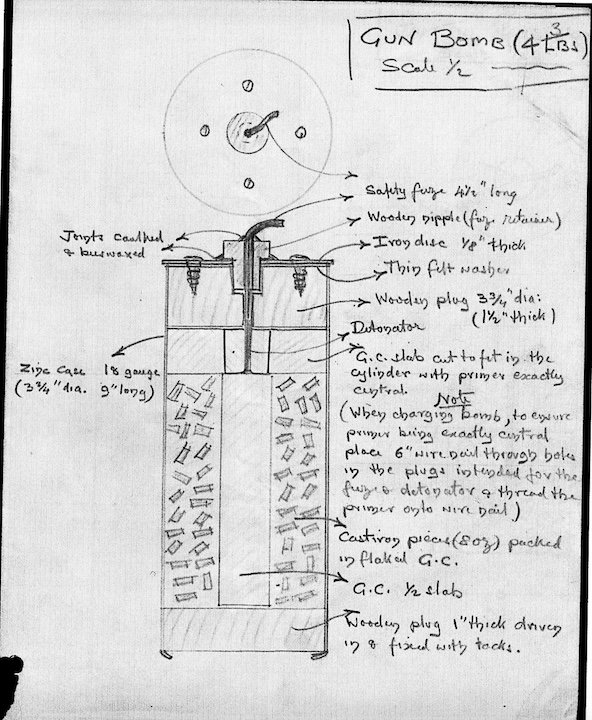

Mortar bomb produced by 20th Company Bombay Sappers and Miners, January 1915. WO/3919: War Diary

The bombs consisted of a tin cylinder, the top and bottom sealed with wooden plugs. Half a slab of gun cotton was carefully centred in the cylinder and packed around with a mixture of flaked gun and small pieces of iron to act as shrapnel. The top wooden plug was drilled to accommodate the detonator, and a wooden nipple was installed to retain the fuse. These bombs were capable of both destruction and anti-personnel. Accuracy and range were improved by ensuring that the cylinders were carefully made to fit snugly in the tube as they slid down to rest on the propellant.

The Introduction of these new weapons brought about significant tactical innovations. The Indian Corps designating their light mortar as an infantry weapon, training infantry as mortar crews, the first being eight men from the 2nd Battalion, The Leicestershire Regiment (Garwhal Brigade), who were attached to the 4th Field company for instruction in the use of the bomb gun on 1 December.

With a new weapon system adding to the infantry's firepower, it was essential to develop a workable management structure to incorporate these new trench mortar crews into the chain of command. After a conference of senior officers, it was agreed that the management and coordination of the Corps' sixteen guns a new position was to be created in the chain of command, the Divisional Mortar Officer who, in turn, was supported by the two Brigade bombing officers who added the management of the eight trench mortars allocated to their Brigade to their list of responsibilities. The responsibility for overseeing the training of the mortar crews lay with the Brigade bombing officers, who had to ensure that each infantry battalion sent sufficient men to the mortar school so that each mortar was provided with four trained men: two forming the active crew and two as reserves or replacements. Under this scheme, an infantry Division could have as many as a hundred infantry trained in the use of trench mortars. Although it is unlikely that such a total was reached in practice, the fact that the requirement existed on paper reflects the Indian Corps' commitment to the new technology. To undertake this training, the Indian Corps developed the first Mortar Training School in the BEF, the firing range completed by the Sappers and Miners on 23 November 1914. When a Division had completed its rotation in the trenches, the mortars and ammunition were treated as trench stores to be handed over to the Divisional Mortar Officer of the incoming Division, who would provide his own gun crews.

A Battle of Mons Photograph. What is wrong with the caption?

STANDARD CAPTION: Troops of A Company 4th Batt. Royal Fusiliers (7th Brigade, 3rd Division), resting in the Grand Place, Mons. The following day the Battalion won two Victoria Crosses (Lieutenant Maurice Dease and Private Sydney Godley) on the Canal bridge at Nimi 2 miles north of Mons.(IWM Q70071)

This image is familiar because of its reproduction in many books and articles relating to the Battle of Mons on 23 August 1914. I have always had problems with the caption, and I will try and explain my concerns.

I accept that the troops in the photograph are A Company 4th Battalion Royal Fusiliers and that they are sitting on the cobbles in the Grand Place in Mons in front of the Town Hall. My problem is the assumption that this image was taken on Saturday 22nd August 1914 while the battalion was on its way to take up positions on the canal.

My contention is that it was taken during the afternoon of Sunday 23rd during the short period when the survivors of the battalion rested in the town to regroup during its fighting withdrawal from the canal where they had been engaged against overwhelming odds since dawn.

My Evidence.

(a) The movements of the battalion on Saturday 22nd August. The march to the Mons Canal from overnight billets at. Le Longueille, beginning at 5:30 am, the battalion acting as advanced guard to the 7th Infantry Brigade. Their orders were to take up an outpost position at Nimmi guarding the crossings of the Canal which they were expected to reach mid-afternoon but were delayed passing through Mons by crowds of cheering inhabitants who loaded the marching troops with presence of eggs, fruit, tobacco, and even handkerchiefs.

(b) Reached the canal in early evening and spent the hours of darkness preparing defences.

The battalion occupied salient created by the Canal between Mons and Nimy:

C Company lay north of Nimy with its right adjoining the 4th Middlesex, and it’s left a little north of Lock 6. Two platoons held Nimy Bridge, two others and Company H.Q. were entrenched at the railway bridge and on the canal bank to the left.

D Company held the position about Lock 6 and the Ghlin-Mons bridge.

B Company lay about Nimy station in support, with Battalion H.Q.

A Company was the battalion reserve north of Mons.

The German attack started in early in the morning with artillery and infantry. By about 11am, it was apparent that the battalion could not hold the enemy and were ordered to prepare to retire. Once consequence of this warning order was that the ammunition boxes were removed from the trenches leading to a shortage of ammunition before the actual order to retire was given at 1.40 pm. ‘C’ Company, the most seriously engaged, lost about 75 men and fell back towards Mons, and when they were clear of their positions ‘D’ Company, which had been covering their withdrawal, also retired to join up with ‘C’ and ‘B’ Companies, with all three retiring towards Mons covered by ‘A’ company as rearguard.

‘A’ company rejoined the rest of the battalion in the Grand Place where the battalion rested for about 15 minutes while the officers and NCOs sorted the men out into their Companies before continuing their retirement. During this time the German infantry was held at bay by the sharpshooters of ‘A’ Company firing down the streets from the cover of houses.

I maintain that the photograph was taken at this time.

As soon as the 4th Royal Fusiliers is left the Grand Place troops of the 84th Regiment, 18th Division, IX Corps entered and rounded up some of the civilians, including the Burgomaster, and drove them in front of them as human shields when they started after the Royal Fusiliers.

Back to the Photograph.

• There are civilians in the photograph, but the majority are men and boys just milling around among the soldiers with no evidence of the cheering crowds handing the soldiers small gifts of tobacco, eggs etc., as recorded when the battalion passed through the town on the Saturday afternoon.

• The soldiers sitting in the Grand Place look exhausted, there is no sign of their packs, rifles close at hand, and many are carrying additional bandoliers of ammunition, something unnecessary on the Saturday when marching to the canal.

These are what one would expect if they were resting after a fighting retreat to get clear of the German infantry and points to the photograph being taken on the afternoon of Sunday 23rd, and not the day before.

We can compare the photograph of the 4th Royal Fusiliers with that of another battalion resting in their way to the canal on the Saturday. Note the different state of their uniforms, that their rifles are stacked not lying at the ready close to the men, and none are carrying extra bandoliers of ammunition