Chapter 3. Part 4.

Grenade Production at Cape Helles.

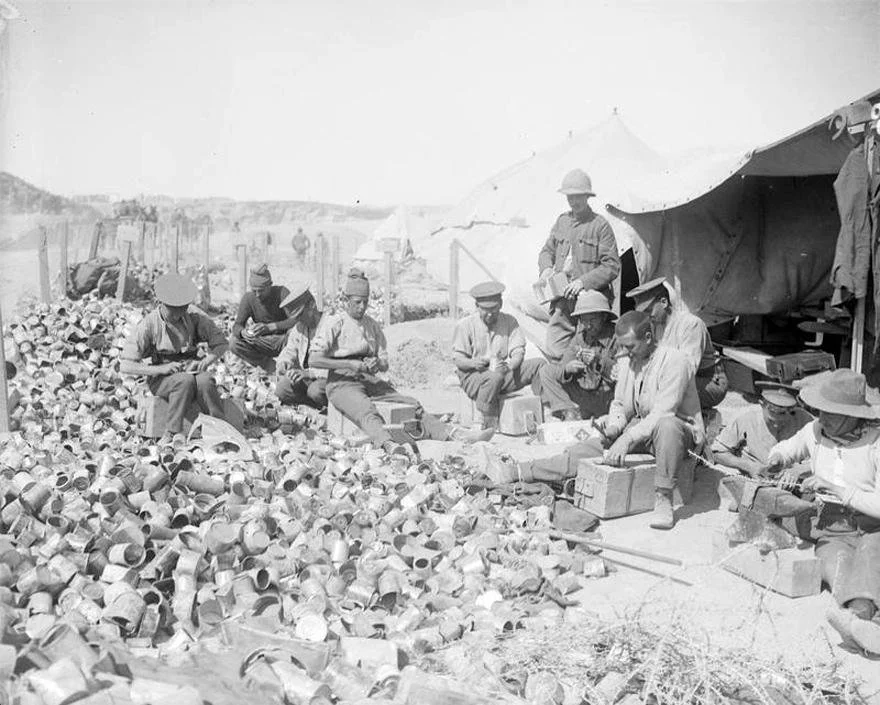

British soldiers making jam pot grenades. Gallipoli 1915. IWM Q13282. Photographer Ernest Brooks

Extemporised Grenade Production at Cape Helles.

When we come to consider extemporised munitions production on Gallipoli, it is crucial to appreciate that the Royal Engineer Field Companies had practically nothing to work with. They lacked the industrial hinterland of northern France, where shaped metal components, machined wood, and simple tools, nails and screws could be easily purchased. On Gallipoli, everything was in short supply, or just not available, and this required the troops, not only those contributing to the manufacture of extemporised weapons, but also the production of almost everything else needed to sustain the army, to exhibit exceptional ingenuity.

Locally produced grenades supplemented those received from the U.K., Malta, and Egypt, and the similarity in the design of the jam-tin and hairbrush hand grenades, and in the organisation of the bomb factories, strongly suggests that the Royal Engineer Field Companies on Gallipoli were familiar with extemporised munitions production in France. Also, as in France, the bomb factories became responsible for the local repairs and maintenance of the trench mortars and trench catapults and manufactured many of the items required for trench warfare, such as periscopes, rifle rests, periscopic rifles, ranging blocks for rifle grenades, and the boxes and containers needed to keep everything in the trench clean and functional.

Extemporised grenades were first produced by the Territorial Field Companies attached to the 29th Division in late April, followed by a training programme for the Field Companies attached to the other Divisions.

While the 29th Division bomb factory remained the best organised and most productive of these early factories, sustaining an average output of 200 to 250 grenades a day in June, it still fell short of divisional needs, as trench-to-trench fighting required many grenades. In one twenty-four-hour period of intense bombing, two battalions expended over 600 grenades.

Following the reorganisation of the troops at Helles into VIII Corps at the beginning of June, Lieutenant-General Hunter-Weston asked the Commander, Royal Engineers 38th Division, to report on munitions production across his new Command, and his report outlined some challenges facing the Royal Engineer Field Companies. A significant factor was a shortage of sappers. Endemic to Gallipoli, typically in summer, was the high level of sickness, and the depleted Field Companies were finding it difficult to allocate men to the bomb factories when there was such a high demand for skilled sappers to carry out essential engineering work, such as the construction of trenches and shelters and the never-ending search for sources of clean water. In addition, it was not uncommon for munitions production to be halted for several days following the withdrawal of the sappers to address an engineering emergency, or due to bad weather or heavy seas preventing the landing of essential components, such as detonators.

There had been attempts to sustain and increase grenade output by employing more infantry, but this had proven to be counterproductive. Experience had shown that unsupervised infantry quickly became confused by the variety of explosives available and produced grenades of poor quality. They also increased the wastage of scarce materials by not packing the explosives properly into the tin cans, by fitting the detonators so loosely that they dropped out when the grenade hit the ground, or by crimping them so tightly to the fuse that it stopped burning before activating the detonator. An additional burden on the existing Divisional bombing schools was that the Field Companies accompanying reinforcements were, like their infantry, practically untrained and with officers unsure of their responsibilities. This made it almost impossible for any newly arrived Division to divert resources to developing a bomb factory or even to train its bombers, and, by default, the responsibility for addressing these deficiencies fell to the experienced staff in the existing bomb factories, especially those of the 29th Division.[1]

In an attempt to improve the situation, and use his resources more effectively, Hunter-Weston separated manufacturing from training, which became the responsibility of the battalion bombing officers, and swept up the manufacture of grenades, and all the other items required for trench warfare, into one enlarged factory at Lancashire Landing under the Officer Commanding, Base Park R.E. This became the depot and issuing authority for everything needed for trench warfare, including the extemporised grenades, issued to the Divisions at Cape Helles in proportion to the tin cans, and scrap iron, they contributed to the manufacturing process.[2]

Hunter-Weston's reorganisation was an improvement, but the most significant changes were to occur after August 8th, when Lieutenant-General F. J. Davies assumed command of VIII Corps during the illness of Hunter-Weston. His transfer from command of the 8th Division on the Western Front brought a wealth of experience in trench warfare and in making the best use of extemporised munitions. Drawing upon his knowledge of the First Army Workshop in Bethune, Davies reorganised the Bombing Factory at Lancashire Landing by creating an improvised self-contained unit termed the VIII Corps Bombing Factory with a permanent establishment of 1 officer, 2 sergeants, three corporals, 24 Sappers and 1 batman. The Sappers included the following tradesmen: six carpenters, three blacksmiths, two wire splitters, two fitters, and two tinsmiths. The high proportion of NCOs was justified because they had to supervise infantry working parties that often exceeded a hundred men daily.[3] If sufficient material was available, the bomb factory was capable of an output of 2,000 to 3,000 grenades a week. In addition, it was responsible for the repair and modification of the trench catapults, the manufacture of all non-munition equipment required in the trenches, and the issue of all explosive ordnance, except artillery shells, across VIII Corps.

Considering the high premium for space at Lancashire Landing, it is a measure of General Davies' commitment to the importance of bombing that he constructed a new grenade training range measuring 860 by 350 yards, inside which was constructed an Ottoman front line trench in all its details, 189 yards long with three communication trenches each 60 yards long. This was used to train bombers with live grenades, and, once a fortnight, a large fatigue party was told off to repair the damage to the trenches inflicted by the grenades. In addition to training the staff of the bombing school was responsible for investigating all bombing accidents, fatal or not, across the Corps, a critical role in maintaining the confidence of bombers in the grenades they handled. In addition to the VIII Corps Bombing Factory, a smaller but similar organisation was developed at ANZAC, while GHQ maintained an Army Grenade School on Mudros that trained officers and men as instructors, gave advanced instruction on the different patterns of grenades, carried out research on captured enemy grenades and explosives, and coordinated the reports of accidents across the whole Command.

Davies' policy across VIII Corps was that all infantry were to be trained in throwing grenades. To achieve this, units were encouraged to nominate their best officers and NCOs for training as bombing instructors, and were rebuked by the Corps Commander if they sent unsuitable candidates. Even with all infantry trained to throw grenades, there was still a need for specialist bombers. These men were identified during routing training as showing a particular aptitude for grenade throwing and appointed to battalion bombing squads consisting of bomb throwers, bomb carriers, bayonet men, and a damper, all of whom underwent six days of advanced training on different types of grenades. This was essential, for it was possible to find battalion bomb stores holding six different patterns of grenade, each with its own characteristic method of lighting. Battalion bombing squads were taught grenade tactics, such as delivering coordinated attacks on enemy positions and the clearing of trenches, traverse by traverse; tactics first evolved on the Western Front.[4] These men trained as a unit and billeted together to develop esprit de Corps and mutual confidence with the very best of them, about 30%, earning the much-coveted special proficiency badge in the form of a grenade.

General Davies introduced two other innovations at Cape Helles, which were also adopted at ANZAC. He chaired a weekly bombing conference of the O.C. Corps Grenade Park and the Divisional bombing officers to address current issues, analyse after-action reports of bombing attacks, and disseminate best practices. For example, the meeting of 13 December dealt with the best way of protecting grenades and fuses from wet weather, the safety of the Mills grenade, received a report on a new type of French grenade and discussed adaptations and modifications to the trench catapults so that they kept a constant range when fired at night.[5] Davies was also aware that the soldiers under his command were capable of coming up with potentially good ideas for the invention and improvement of equipment that never saw the light of day, as there was no mechanism that allowed them to do so. To harvest these ideas, he set up an Inventions Committee, chaired by the O.C. Grenade Park, to consider any ideas put forward, conduct experiments on promising ones, and collect reports and feedback on modifications introduced by the troops to munitions already in use. Battalion commanders were instructed to include details of the Committee in daily orders and to encourage their men to bring their ideas forward, even putting in place mechanisms to protect the intellectual property of soldier inventors.[6]

[1] TNA: WO95/4273: VIII Corps. GHQ War Diary 25 May 1915

[2] Ditto, 27 May

[3] AWM4. 1/17/2. Part 2: G.H.Q. Dardanelles Army. Memo to Chief of the General Staff. MEF.6 December 1915

[4] TNA: WO95/ 4305: General Staff. 29th Division. Suggested syllabus for a six-day course of Instruction at Divisional Grenade Schools. August 1915. Appendix 7

[5] TNA: WO95/4274: General Staff. VIII Corps. Bomb Conference 12-12-15. Appendix XXXI

[6] TNA: WO95/4274: General Staff. VIII Corps. Inventions Committee. December 1915. Appendix XXXVI