Chapter 3. Part 2. The Supply of Grenades.

The attritional trench warfare seen at Cape Helles took the form of a continuous series of small local battles, required the provision and employment of many men trained as bombers and supplied with an adequate number of grenades. From about August onwards, there appear to have been sufficient grenades from all sources to organise an effective supply system for the troops in the front line and the bombing stations to respond to an enemy infantry attack. Daily usage at the Front was replaced by a Brigade reserve of 1000, which in turn was supported by a Divisional reserve of 500 maintained at the bombing school or Divisional Engineering dump, and re-stocked daily from the Corps grenade factory, which held supplies of all available grenades. When in the fire trenches, each battalion, in addition to supporting the grenadiers at the bombing stations in the saps, had to maintain two bombing squads, with their grenade packs fully stocked and held close at hand, ready to repel an enemy attack. Other full packs were stored at the Divisional Grenade School and issued to bombing parties going forward to reinforce the front line if the enemy attacked, or to mount a counterattack if the enemy had broken in. As a last resort to prevent an enemy breakthrough, the staff and the men under training in the Grenade School served as the Division's final reserves.[1] At particularly critical parts of the line, for example at Border Barricade where the trench was shared with the enemy, more elaborate constructions were developed consisting of a deep dugout to shelter and protect the garrison with a strong bomb-proof barricade facing the enemy and, in its instructions on these larger bombing stations, the 29th Division laid down that there must be at least six trained grenadiers at each station and their supply of grenades must never fall below a 100, with a reserve of another hundred for each bombing station at battalion headquarters.[2]

The War Office appears to have treated the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force as a dumping ground for surplus munitions and other items of equipment no longer required by the BEF, having become redundant through replacement by newer equipment. This pattern of supply is clearly seen in the delivery of grenades, such as the double cylinder and the Ball hand grenades, in significant numbers only after they had been withdrawn from service on the Western Front. Munition supply from Britain tended to be irregular and interrupted by enemy submarine activity and bad weather that prevented the landing of supplies on the exposed beaches of the peninsula.

The War Office. The No 1 Percussion & Hales Rifle Grenades.

By April 1915, the War Office had delivered a small number of the No. 1 percussion hand grenade and the Hales rifle grenade to Hamilton's force in Egypt. However, since the manufacturer failed to meet the BEF's needs, only token numbers reached the Dardanelles. On May 9th, the 29th Division supplied the Indian Brigade with cane-handled hand grenades. Later, it distributed 125 more to the Indian Brigade, 125 to the 87th Brigade, 50 to the 88th Brigade, and 25 to the Border Regiment, retaining 400 as a reserve.[3] ANZAC also received grenades from the same shipment for the 1st Australian Division and notified its battalions that the engineers would provide instructions before issue.[4] The ANZAC troops strongly dislike this percussion grenades,

General Staff ANZA

5/10/15.

Memorandum

We have on the beach nearly 900 Hales rifle grenades and over 2400 Cane Handled No.2.

he Hales rifle grenade has to be fired from a rifle held at an angle of about 45 degrees. If the butt is put on the ground - it works well but we cannot do this in our deep trenches. If placed to the shoulder the rifle kicks very badly.Result the men dislike it and will not use it trench fighting. I suggest that what we have should be sent away an Ordinance asked to send us no more of this type.

The Cane Handled No.2 seldom detonates if it hits what it is aimed at. This is because if it hits the parapet the parapet is generally soft and will not resist significantly to explode the grenade, and if it hits the trench, it hits the side at an angle, glances off, and falls at an angle. It is also difficult to throw out of a deep trench. The men distrust and dislike it and will not use it, and I suggest that these are also sent away and Ordinance us to send us no more of this typ

2. Cricket ball, Malta it is very heavy too heavy for men to continue throwing, or to be throwing any distance. This might be brought to notice.[5]

The Trench Warfare Department.

We have some information about deliveries of grenades produced by the Trench Warfare Department later in the year, from a scribbled note on the front cover of a copy of 'Memorandum on the Training and Employment of Grenadiers' made by an anonymous Staff Officer in June 1915, listing the No 13, Pitcher and Cricket Ball grenades.[6] Another scribbled note on the back cover of an instruction manual for the Garland Mortar lists 50,000 unfilled double cylinder and 1,600 Ball grenades.[7] It is impossible to determine the origin of the unfilled grenades, which could have come from the U.K. or were copies produced in the Cairo Citadel. In either case, the assumption is that they would be filled with explosives and fitted with fuses and detonators either on Lemnos, the main supply base of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, or by the Divisional bomb factories established on the Peninsula.

The Malta Grenades.

The Malta grenade, a local copy of the No. 22 Ball Grenade, was produced in response to Hamilton's March letter. Production started in August 1915: a cast-iron bomb, a quarter of an inch thick and two and three-quarters inches in diameter, cast and machined at the Carlo Place foundry in Hamrun.

The Maltese Grenade. Imperial War Museum MUN 3273.

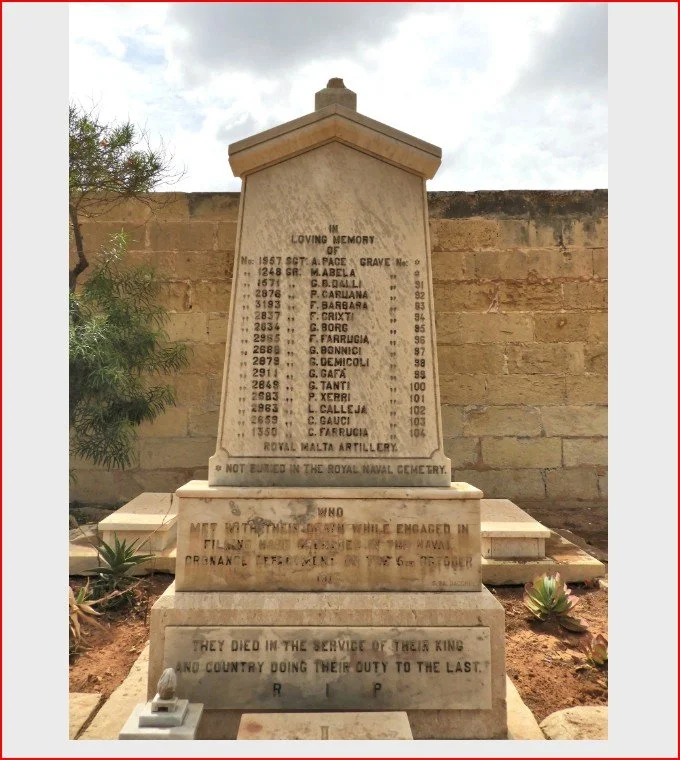

The grenade bodies were then transported to a makeshift filling station established in tents in the Naval Ordnance section of H.M. Dockyard, where 50 volunteers from the Royal Malta Artillery, a Territorial unit, filled them with gun cotton before sealing them with a brass plug drilled to take a fuse and detonator. On 5 October 1915, after about 68,000 had been manufactured, a stock of about 120 grenades exploded, quickly followed by two smaller explosions that left sixteen of the volunteer gunners dead and another sixteen wounded. Naval and military personnel, as well as French sailors, assisted the injured with a French Naval priest administering the last rites to the dead and dying. Production ceased after this accident.

The Memorial to the fatalities of the explosion of 5 October 1915. All but 2 are buried in the Naval Cemetery, Kalkara, Malta. https://www.facebook.com/combatarchives

The Egyptian Grenades.

In addition to the Garland grenade thrower discussed below, the Citadel in Cairo turned its hand to grenade manufacture, although precise details of what they produced are lacking. References in various war diaries suggest they were copies of the Ball and Double Cylinder grenades and were less safe than the originals due to defective workmanship and quality control. We do not know how many grenades Cairo produced, but their output, combined with that of Malta, appears to have been high enough to upset the Western Front clique in the War Office, who complained that such large quantities of high explosives were being sent to the Mediterranean to make grenades that it was interfering with home production. The War Office wrote to Sir Ian Hamilton asking him to stop making grenades, promising in return a regular guaranteed delivery of 30 to 40,000 a week from home. An empty promise that Hamilton quite rightly ignored.[8]

The Mills Grenade.

With design and production difficulties delaying the introduction of the Mills, the first trial batches of the No. 5 Mark I did not reach Gallipoli until the beginning of September 1915. First impressions were positive,

the new Mills hand grenade tried with excellent results. It is the simplest, safest and most effective bomb yet seen here.[9]

Unfortunately, the first substantial delivery in October appears to have included examples of defective manufacture. Once training started, the VIII Corps bombing school reported that the rate of accidents with this grenade was exceptionally high for the small number used. At about the same time, presumably in response to information from the War Office on the manufacturing defects, ANZAC HQ issued urgent instructions that bombers must take great care to prevent the lever from moving after withdrawing the safe pin.[10] The VIII Corps monthly bombing conference in November discussed the safety issues, the O. C. Bombing School reporting that, as a consequence of the accidents, the grenade was gaining a bad reputation among the bombers, with many refusing to use it, and suggested suspending training until they received further advice from the War Office. December saw the delivery of the improved version of the Mills grenade, with the O.C. bombing school reporting no accidents in training, and the bombers now declaring that it was the best grenade they had ever seen. However, supplies were very limited due to the break in production while the faults were corrected, and the priority given to supplying the BEF, so very few Mills reached the peninsula over the period October to December 1915. Their use at Cape Helles was so restricted that authorisation from the Corps Commander was required before any could be issued, and even then, they were limited to night patrols.[11]

[1] TNA: WO 95/ 4304: General Staff. 29th Division. Proposals for Organisation of Grenadiers and for Reserves of Grenades. August 1915. Appendix A

[2] TNA: WO 95/ 4304: General Staff. 29th Division. War Diary. August 1915. Appendix 7

[3] TNA: WO 95/ 4304: GHQ 29th Division. Commander Royal Engineers. War Diary, Entries for 7,9, and 20 May 1915

[4] AWM4. 1/42/4 Part 1: GHQ. 1st Australian Division. War Diary, 5 May 1915

[5] AWM25/115/42

[6] AWM4. 1/25/3. Part 3: General Headquarters. ANZAC. Corps. War Diary, June 1915. Appendix 7a

[7] TNA: WO95/4273: General Staff. VIII Corps. May- Sept.1915. The Garland Grenade and Howitzer. Particulars of Construction and Use. (Cairo: War Office Printing Press. 1915)

[8] Hamilton, Gallipoli Diary. Vol.1. p.156

[9] AWM4. 1/42/8 Part 1: General Staff HQ. 1st Australian Division. War Diary, September 1915. Appendix No. 1

[10] AWM4. 23/4/3: 4th Infantry Brigade Sept.-Nov. 1915. War Diary, Entry 4 November.

[11] TNA: WO95/4273: General Staff. VIII Corps. War Diary, Bombing Conference.14 December.